Rethinking Grading

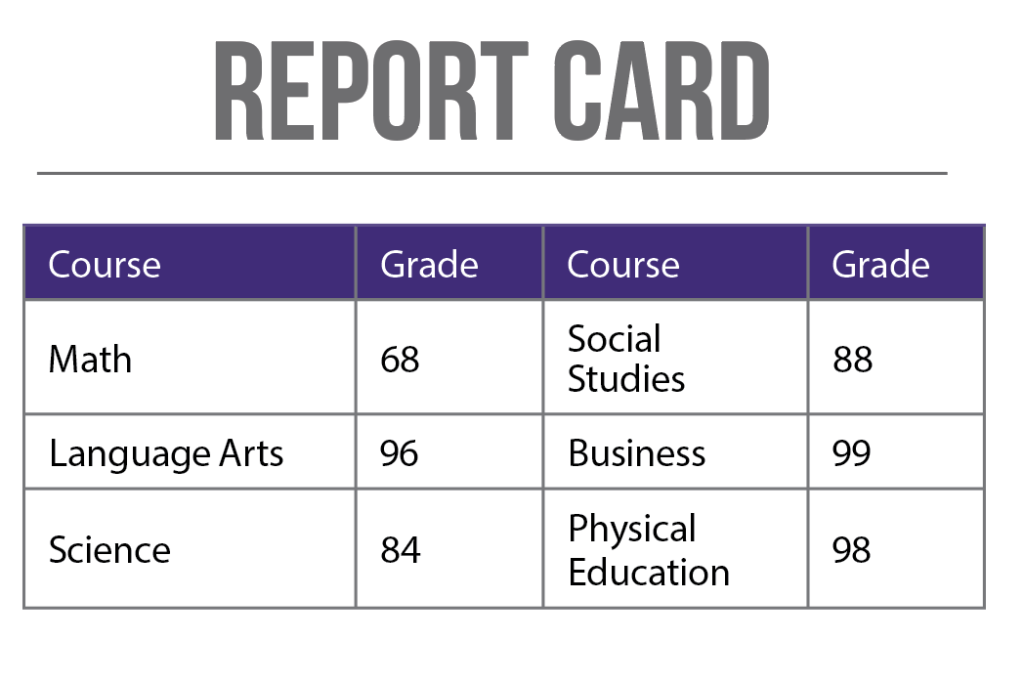

A student receives his third-quarter report card:

Internally, he translates this to three As, two Bs, and a D—based on a 10-point reporting system. He shoves the report card into a notebook, gets it signed by a parent, and returns it to school the following day.

All traditional boxes have been checked:

- Grades were assigned.

- Grades were communicated to parents.

- Report card was signed and returned.

Unfortunately, all too often grades are points on paper used to determine rewards, athletic eligibility, and/or class rank. How frequently—and universally—do students, teachers, and school leaders use grades as reflection points to identify areas for growth and to make a plan for strengthening learning? How many parents—and students and staff, for that matter—know what earning a 96% in a Language Arts course really means on a report card? What are schools doing with students scoring a 68% in math? Let’s explore how grading best practices can better inform and ensure learning for all students.

Best Practices and Strategies to Consider

If 10 teachers were asked to describe their grading practices, you might receive 12 different answers; these teachers could even be in the same state, district, or school. I would argue that teachers and school leaders don’t have to agree on every component of grading, but that a child’s grade should reflect mastery of the content being delivered. Research-based best practices for grading can be found in multiple studies and texts, including Rick Wormeli’s book Fair Isn’t Always Equal: Assessing and Grading in the Differentiated Classroom. School leaders and teachers should reflect on their current practices and make decisions about the makeup of a student’s grade. Not all activities relate to mastery, which leads to questions about the validity and reliability of grades. Consider:

- Homework

- Behavior

- Attendance

- Participation

- Extra credit

- Compliance activities (e.g., the student returned a signed report card for a free “100”)

- Class supplies (e.g., the student brought hand sanitizer for the classroom for a free “100”)

One evolving strategy to help schools focus explicitly on academic mastery and encourage positive behavior is to include a soft skills report card along with a traditional report card. Soft skills report cards can be rubric-based and include metrics such as:

- Work habits

- Collaboration/participation

- Respect

- Initiative

- Homework completion

- Any other area the school deems appropriate

Rubrics and Standards-Based Grading

As educators, we often hear a student say something to the effect of, “What do I need to do on this assignment to (pass, get an A, get a 100)?” This question—and its many variations—can quickly be answered by providing students a rubric outlining learning expectations. Rubrics allow students to take ownership of their grade and more importantly, their learning.

When students and families see a grade on an interim report, they often do not understand its relation to overall learning. Sometimes, the teacher also may not recall what an assignment measured. Standards-based grading ensures a focus on learning, rather than on compliance. With this approach, students are not measured relative to one another; they are measured on their mastery of standards.

Common Formative Assessments and Grading

Common formative assessments (CFAs) are vital to ensure learning is taking place in the classroom. CFAs serve as temperature checks, allowing teachers to quickly measure what concepts and topics students have mastered and which standards and skills the whole class or certain students need additional time to focus on. Few teachers would argue the benefits, necessity, and use of CFAs to drive learning and instruction—the debate comes with recording results of CFAs. Some teachers would argue that CFAs should be graded and entered into the gradebook. This practice would embrace the philosophy that all students learn at the same rate—which we know is not true.

A CFA can be viewed as a two-way street—it can illustrate a student’s progress toward learning the standards and skills but also a teacher’s success in teaching to those standards and skills. Just as a CFA identifies strengths and weaknesses for students, it can do the same for teachers, providing reflection opportunities and spurring conversations in professional learning communities about instructional practices.

Student Involvement

Student-led conferences are a powerful example of students taking ownership and responsibility for their grades. During traditional parent-teacher conferences, the student is often not even in attendance! With student-led conferencing, the youth takes center stage to explain the “why” behind the grade and is part of the problem-solving process for moving toward mastery. For example, the student would lead the discussion explaining how he was able to be successful in most classes but would spend more time going through individual grades for math class to identify areas for improvement in conjunction with parents and teachers. This provides an opportunity for the student and stakeholders to be on the same page, to set goals, to celebrate successes, and to discuss any intervention or remediation needed to improve the student’s math understanding.

Best Practices and Strategies to Consider

As noted earlier, grading practices are derived from many influences—personal and professional. While there is no one-size-fits-all approach to grading, it is imperative for educators, schools, and districts to reflect on and continually improve their grading practices in order to ensure mastery is being communicated to families.

For one student, the 68% may mean he is grounded at home until his grade increases, but how is he going to improve his grade? If learning is our primary focus, grades should not be final points. We must use grades as indicators and jumping-off points for problem-solving. A student may need remediation at some point during or after the school day to fill standards-based gaps. Perhaps the student has skill gaps that need to be filled and continuously measured during an intervention block within the school day. If neither of these interventions lead to increased mastery, examine why the student received the 68%. At that point, it is pivotal for teachers to reflect upon and improve their grading practices in order to ensure mastery is truly being measured accurately.

Grading Reflections and Conversations

Schools truly focusing on learning and students will ensure their mission, vision, and values align with their grading practices. If they don’t align, conversations must begin. These are not easy conversations for school leaders to facilitate, but they are conversations that need to occur within a school-based team. This team should be composed of teachers, instructional support staff, and administrators—be sure to include some resistors and staff who will “push back.” You want to ensure all perspectives will be discussed and heard to arrive at best practices for the school. As noted earlier, Fair Isn’t Always Equal is a great text in which to ground conversations. Consider inviting a professor specializing in measurement and assessment to periodically join your team (remotely or in person) to offer suggestions. Plan to disclose data with the team, ground ideas in research, and share final outcomes of guidelines and expectations with all staff before implementation.

With these strategies and parameters, students will have a much deeper understanding of the true meaning behind each of their grades. And while grading can be a divisive and polarizing issue, it is vital that districts and schools dive into grading conversations to ensure grades are purposeful, intentional, and focused on exhibiting, improving, and celebrating learning.

Chris Bennett, EdD, is a former principal and current executive director of Middle School Instruction for Gaston County School District in Gastonia, NC.