Addressing the Effects of the Pandemic on Educators

The enduring pandemic has put a spotlight on the interdependence between physical and mental health and learning. Although we are rightfully alarmed about the detrimental effects of COVID-19 on student and family outcomes, as well as the disproportionate impact of this public health crisis on communities of color, the pandemic’s physical and emotional toll on teachers and school leaders has recently become a focus of discussion. Concentrating on the “whole educator” is justified given the longstanding difficulties with teacher retention, workforce diversity, and the breadth of preprofessional training that existed pre-pandemic and has been exacerbated since. Palpable stressors related to increased COVID-19 exposure, demands around intermittent remote learning, and adjusting to ever-changing school health mandates have caused heightened worry and frustration among many education leaders.

Despite many competing priorities to maintain school health and safety, a 2022–23 return-to-school plan will be incomplete without specific provisions to amplify teacher well-being. “Teacher well-being” is a nebulous term, but a review of the literature, as well as our own research with K–12 educators, indicates that a diverse group of factors affect teacher well-being: an interaction between an individual’s sense of meaning/purpose, efficacy, resilience, and school-level contextual factors including cultures of care, responsive and supportive leadership, and respect for teachers as autonomous professionals.

Common approaches to supporting teacher well-being have concentrated on changes to teacher knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors around self-care practices and preventing burnout. Yet, a singular focus on individual change underestimates the role that social and environmental factors play in driving individual behaviors. It also places the responsibility squarely on the teacher to reduce stress and manage contributing factors existing outside of their control. Alternatively, school leaders can leverage systemic organizational practices to encourage positive individual choices and bolster their effects.

In “Sustaining a Sense of Success: The Protective Role of Teacher Working Conditions During the COVID-19 Pandemic,” a study involving 7,841 teachers across 206 schools and nine states, researchers report that strong communication, targeted training, meaningful collaboration, fair expectations, and authentic recognition were essential to teachers’ definitions of supportive working conditions. Unfortunately, guidance on how to create this sense of support and promote a comprehensive teacher wellness strategy is scant, increasing the probability of an ineffective piecemeal approach.

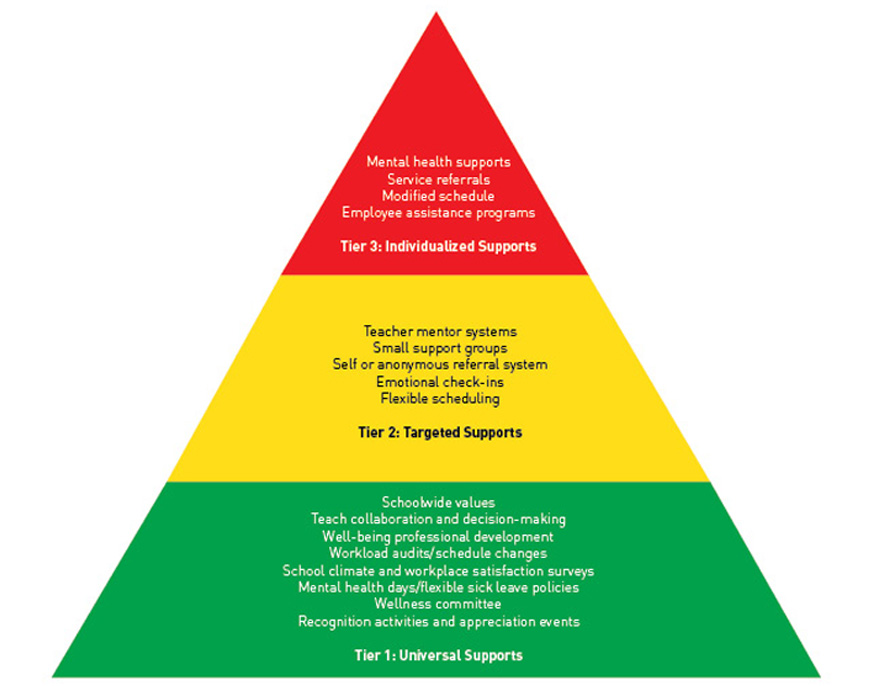

A wellness strategy that accentuates health-promoting environments requires deliberate ways to mitigate a diverse set of teacher-related stressors, many of which school leaders may be unable to easily discern. Using a common organizational framework to address the academic, behavioral, and social-emotional needs of students, much like a multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS) framework, can make ambitious goals for comprehensive teacher well-being achievable.

Providing a continuum of supports reflects teachers’ varied needs throughout the different phases of the pandemic. For example, in our study conducted during the fall and winter of the 2020–21 school year, some teachers indicated a low need for supplemental assistance. Some stated, “I do think [during the COVID-19 pandemic] that our staff has really excelled at working together, being resourceful, helping each other, and dividing and sharing the workload.” Others reported being highly stressed and overwhelmed, signaling the need for more aid from their leaders and school community with statements such as, “Since COVID-19, I am exhausted, angry, and wishing I had chosen a different profession,” and “It is demoralizing when educators feel the weight of endless demands and feel unsupported by those they ought to be able to rely on.”

Applying an MTSS Framework

MTSS employs a proactive and data-driven approach for implementing interventions that foster the conditions for teaching and learning to occur. Although traditionally used to assist struggling students, this approach can also facilitate adult well-being and inform the array of interventions to serve all, some, or a few of the members of a school community. The three tiers of the MTSS framework and key questions that school leaders and teachers can jointly explore to tailor interventions to each school’s unique context include:

Tier 1, also considered universal supports, involves activities designed to enable healthy development, resilience, and relationship-building across the school to build connectedness and positive coping, especially when the level of risk is unidentified. Questions to consider:

- What should be made available for all teachers as they navigate a stressful year, regardless of visible signs of stress or known challenges?

- What activities can we promote that reflect our schoolwide values for creating a safe, nurturing, and engaging environment as we transition to a new year?

Tier 2, targeted interventions sometimes delivered in small groups, are for those who have been reliably identified as having emerging challenges or mild to moderate symptoms that interfere with daily functioning. Questions to consider:

- What methods and channels are available to teachers to identify themselves or a colleague for whom they are concerned?

- What challenges are best addressed by bringing together those with similar struggles?

Tier 3, or intensive supports, are for educators with significant challenges who have not benefited sufficiently from Tier 1 or 2 supports and need more intensive, individualized interventions. The aim is to reduce the severity or frequency of their challenges and treat troubling symptoms. Questions to consider:

- What resources can be made available for teachers who manifest more severe challenges in their return to school or who are experiencing an acute crisis?

- How can intensive interventions be confidentially delivered and reliably accessed by those who need them?

Strategically Reducing the Impact of the Pandemic

By drawing on the resources available in and out of the school, a successful post-pandemic recovery plan can be executed. The summer is an ideal time for school leaders to consider their four Ps: the people, programs, practices, and policies in their school community.

People: The people affiliated with school possess skills and expertise that can be used in the execution of a teacher well-being approach. Educators and administrators, health professionals, community partners, parents, volunteers, and students can all contribute to the development of a comprehensive teacher wellness strategy.

Programs: Schools offer programs that reinforce life skills, develop competence, promote healthy development, and teach positive coping. These programs that advance physical, behavioral, and emotional health—and are typically directed to students and their families—can be adapted for teachers.

Practices: A school’s culture is defined by the shared beliefs, values, and attitudes of the members of the school, along with the behaviors shaped by those values and beliefs. It is important to establish schoolwide expectations and norms about wellness. And these expectations should inform school protocols and plans.

Policies: Health and education-related policies articulate what can and should happen in schools and establish the structures to implement effective wellness-related programs and practices.

Overlaying MTSS and the 4 Ps

Many people can help cultivate a restorative environment in a post-COVID educational setting. Examples of the people, programs, practices, and policies delivered across multiple intervention levels and available to all teachers in the school are outlined in the figure below.

Tier 1: Universal supports available to all teachers and staff

- Explicitly state and continually promote school values about health and well-being, positive relationships, and collegial support.

- Recognize individual strengths and competencies among teachers and facilitate opportunities for them to showcase personal and professional assets.

- Develop a school wellness team/committee that incorporates discussion of teacher wellness activities and gaps.

- Conduct schoolwide mindfulness moments or one-minute breathing exercises.

- Regularly assess (e.g., through surveys, focus groups, individual check-ins, etc.) teacher needs and solicit input on desirable well-being strategies.

- Champion the inclusion of mental health days or flexible sick leave policies.

Tier 2: Targeted supports for teachers and staff with emerging or less-intense needs

- Institute a teacher buddy system, linking newer teachers with veteran teachers or those with mastery in one area (e.g., classroom management) with those seeking guidance in that area.

- Offer support groups directed by teachers’ interests and needs, especially for those from marginalized groups, to safely discuss and address discriminatory practices or microaggressions experienced in the workplace.

- Conduct emotional check-ins at meetings to identify individual and/or group struggles.

- Create and disseminate protocols for referring oneself or a colleague when concerns arise.

Tier 3: Intensive supports for teachers and staff with more acute or severe needs

- Organize on-site therapeutic services for teachers.

- Communicate the importance of help-seeking and the value of reducing stigma around behavioral health treatment.

- Execute formal agreements with community partners to refer teachers experiencing mental illness symptoms.

The expectation is not that school leaders be solely responsible for the design, implementation, evaluation, refinement, and sustainability of a comprehensive teacher wellness strategy. Rather, school leaders can invite multi-disciplinary school-connected partners, and their respective networks and resources, to actively collaborate and jointly implement this goal.

Unique Needs of BIPOC Educators

All teachers have operated under extraordinarily difficult circumstances, but the added stress of identifying as a Black, Indigenous, or People of Color (BIPOC) educator during the last two years is significant. The cumulative traumas associated with the pandemic, racialized violence, and other forms of systemic oppression and discrimination require a safe space for validating, processing, and problem-solving these experiences.

In their report, “If You Listen, We Will Stay: Why Teachers of Color Leave and How to Disrupt Teacher Turnover,” Davis Dixon, Ashley Griffin, and Mark Teoh highlight the significant damage caused by workplace environments that leave teachers of color feeling invisible and devalued, and they outline steps that schools, districts, and state agencies can employ to successfully retain them. Similarly, researchers Deirdre Johnson Burel, Felicia Owo-Grant, and Michael Tapscott share firsthand perspectives of BIPOC education leaders in their article, “Real Talk: Teaching and Leading While BIPOC,” and urge school and district leaders to take heed of BIPOC educators’ needs while also recognizing the unique strengths of teachers and leaders of color in improving conditions for teaching and learning during times of adversity.

Teacher well-being is a critical component of any successful school-based health initiative, as school leaders help their schools navigate through the ongoing pandemic and into a future that is vulnerable to continued COVID-related challenges. A comprehensive strategy to support teacher wellness that accounts for the influence of both individual and school-level factors can create a safety net for all teachers.

The most successful comprehensive plans for teacher well-being will be those based on an MTSS approach. Such an approach enables school leaders to reinforce individual choices for self-care by institutionalizing system-level interventions and by collaborating with school-community partners to benefit all adults in the building.

Olga Acosta Price, PhD, is an associate professor in the Department of Prevention and Community Health at the Milken Institute School of Public Health at The George Washington University (GW). Beth Tuckwiller, PhD, is an associate professor of special education and disability studies at GW and a center associate at GW’s Center for Health and Health Care in Schools. Jennifer Clayton, PhD, is an associate professor of educational leadership and administration at GW. Harriet Fox, PhD, is a visiting faculty member in special education and disability studies at GW. Rachel Sadlon, MPH, is an associate director of research and evaluation at GW’s Center for Health and Health Care in Schools. Shruthi Shree Nagarajan, MEd, is a graduate research assistant at the Graduate School of Education and Human Development at GW.