Advocacy Agenda: February 2021

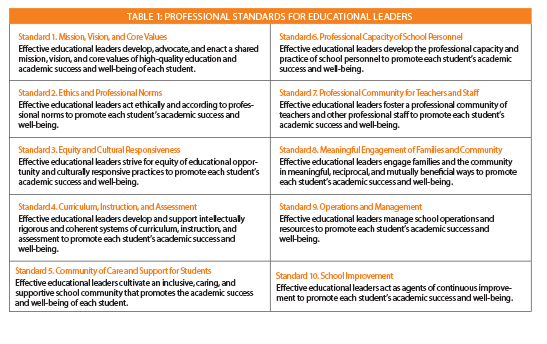

The Professional Standards for Educational Leaders (PSEL) document provides foundational principles to guide the practice of educational leaders and ensure they are ready to effectively meet challenges as education, schools, and society continue to transform. The PSEL are designed to improve student learning and achieve more equitable outcomes for all students and are grounded in more than 600 empirical research studies and the contributions of over 1,000 practicing educational leaders.

At their board meeting in June 2020, the National Policy Board for Educational Administration (NPBEA) made the decision that advocating for the adoption or adaptation of the PSEL is its No. 1 priority.

Why Are the PSEL Important?

The PSEL reflect research-informed actions that are central to the needs of today’s schools and function as a framework for principals. While all domains of leadership are important, principals have the flexibility to choose what is most relevant to their context and particular situation. Principal supervisors use the PSEL to guide conversations with principals during goal setting and professional development.

The PSEL target principals’ practice toward student success as well as their social, emotional, and psychological well-being. According to “What the New Educational Leadership Standards Really Mean” in the May 2016 issue of Principal Leadership, “The PSEL were designed intentionally to address the concern for each student. The standards direct principals’ practices toward two foundational pillars of success—academic press and care and support,” noted authors Joseph Murphy, chair of the PSEL standards committee at Vanderbilt University, and Mark Smylie, who co-chaired the PSEL Workgroup Writing Committee at the University of Illinois-Chicago. “Academic press refers to the effort to challenge students to develop academic knowledge and skills required for student success in school and beyond. It includes high expectations, the opportunity to learn, and intellectually rigorous teaching. Care and support for students creates conditions conducive to academic success and well-being, like physical and psychological safety, trust, a sense of respect, value, and belonging, as well as services and accommodations to meet learning needs. PSEL tells principals that if they focus on efficacious combinations of press and support, schools can become powerful relational communities, and students will achieve substantial success.”

Advocating for the PSEL

When states and districts intentionally utilize a set of research- and practitioner-informed leadership standards, they provide critical direction for school leaders and inform their work on behalf of students.

“Understanding and Addressing Principal Turnover: A Review of the Research,” a collaborative study conducted by the Learning Policy Institute (LPI) and NASSP, confirmed this: “Principal turnover is a serious issue across the country. A 2017 national survey of public school principals found that, overall, approximately 18 percent of principals had left their position since the year before. In high-poverty schools, the turnover rate was 21 percent.”

According to the study, the principals interviewed were passionate about their work; however, they acknowledged the complexity and daily demands that often make their jobs quite challenging. Many cited poor working conditions, being undervalued for their work, having too little authority to make certain decisions for their schools, and accountability systems that do not support continuous growth. When districts and states provide PSEL-aligned induction programs, mentoring and coaching support, and specific job-embedded professional learning, school leaders feel supported and valued, which leads to less turnover.

How does advocacy for the PSEL relate to the challenge of principal turnover? States and districts that invest in equity-centered principal pipeline programs demonstrate to the education community that investing in principal leadership is central to school improvement and student success.

The PSEL present a “theory of action.” Standards should be integrated into selective hiring practices, principal induction, performance evaluation, principal supervision, and leader tracking systems. To this end, many states have developed models of principal performance evaluation aligned to the PSEL or adapted state standards for school leadership. For example, the Delaware Department of Education convened a group of principals and principal supervisors to design a PSEL-aligned performance rubric that is used statewide for principal and assistant principal evaluation. Kentucky has just implemented its new performance evaluation system aligned to PSEL as well. Using PSEL allows the standards to “guide the operationalization of practice and outcomes for leadership development and evaluation,” according to the NPBEA.

Action Steps

It’s no surprise that the NPBEA moved to make advocating for PSEL its No. 1 priority. The executive directors of these professional organizations—who represent thousands of educational leaders who are engaged in preparation and practice—determined that the PSEL are essential to guiding and supporting the complex work of school and district leaders. Aligning a state and district system to the standards is the first step in creating a pipeline of equity-centered school leaders. These action steps can help education leaders create a standards-aligned system for school leadership:

Ask questions. Many times action takes place because someone asks the right question. Consider asking your district and state policy leaders:

1. Does our state have an adopted set of educational leadership standards? If not, when can we expect them? If yes, then:

- How do the standards influence university preparation programs?

- Is there a recommended standards-aligned performance evaluation system?

- Is there funding for districts to create an equity-centered principal pipeline program aligned to the standards?

2. Does my district adhere to the state-adopted educational leadership standards? If yes, then:

- Do we have a standards-aligned performance evaluation system?

- How is my professional development aligned to the standards and the growth goals of the school leader?

- How is recruitment and selection of assistant principals and principals informed by the standards?

Get involved. Volunteer to serve on a committee or task force.

- Ask to serve on a state committee focused on principal turnover, performance evaluation, and standards development.

- Join a local affiliate organization for NASSP; the National Association of Elementary School Principals (NAESP); or AASA, The School Superintendents Association. These organizations have advocacy opportunities and often meet with national and state legislators to recommend policy related to state and national standards and principal pipeline funding.

- Ask your superintendent or the principal supervisor if your district has a principal pipeline or succession planning committee. Volunteer to chair the committee.

Read and research. Conduct your own action research project so you learn more about the importance of national standards as the foundation of preparation and practice of effective school leadership.

Initiate change. Leadership involves identifying problems and creating solutions. If your state or district does not have a set of educational leadership standards, then advocate change by:

- Creating a professional learning network over social media to learn what colleagues in other states and districts are doing

- Writing an article or blog for NASSP, NAESP, or AASA to advocate for the change you have identified

- Recording a podcast and sharing it with your Twitter feed

- Working with your local affiliate at NASSP, NAESP, and AASA and joining their advocacy campaign

For more information on the PSEL, visit www.npbea.org.

Jacquelyn Owens Wilson, EdD, is the executive director of the National Policy Board for School Administration based in Reston, VA, and the director of the Delaware Academy for School Leadership, College of Education and Human Development, University of Delaware in Newark.