Student Centered: January 2021

As educators, we are continually examining our individual and collective practices to improve our students’ educational outcomes. We recognize that an approach that seeks to support the whole child by addressing academic, social, and emotional growth—while also attending to the nonacademic needs of students and their families—is needed.

Every school has the information available to engage in this work; they just need to ask their students. Children and teens are often eager to share their insights. “NO ONE understands the experience of schools better than the students who are living it,” note students who participated in student focus groups that occurred in the Southeast from 2018–20.

Gathering Student Voice: The Process

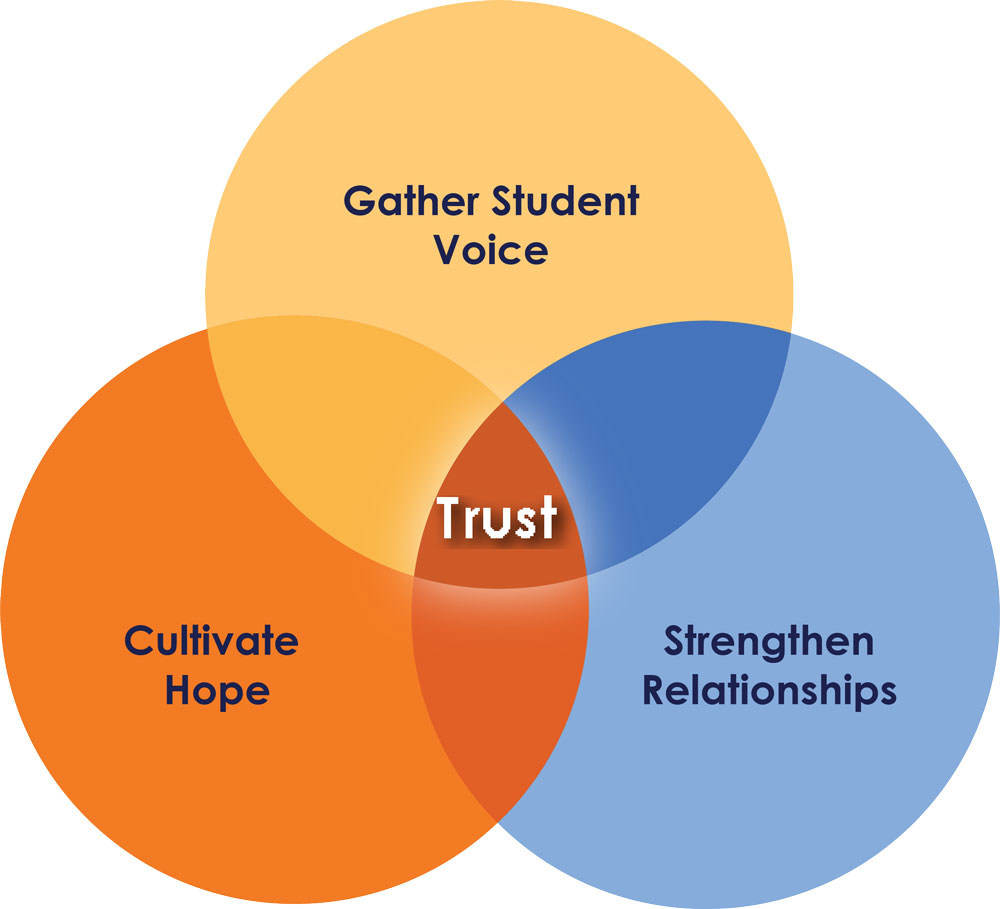

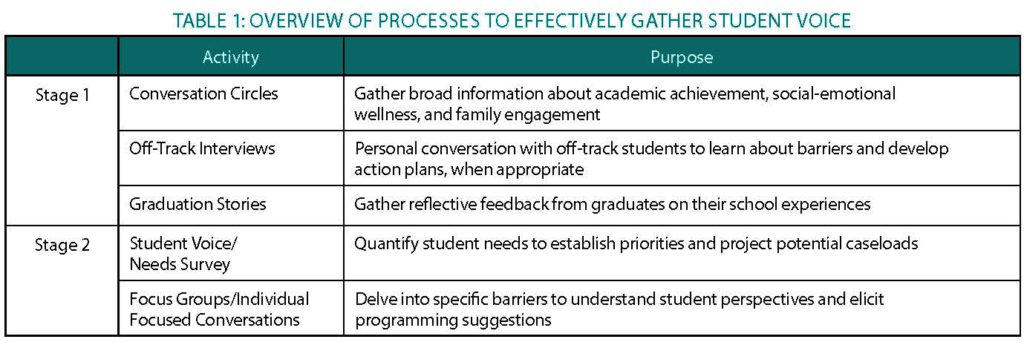

Gathering student voice requires the desire to strengthen relationships through a facilitative approach akin to motivational interviewing—a form of dialogue. Empathy is at the heart of motivational interviewing, requiring the interviewer to shift from a prescriptive approach, where they are the expert giving advice, to a collaborative approach, where they treat students as partners with a shared mission of positive change, note Sylvie Naar-King and Mariann Suarez in their book Motivational Interviewing with Adolescents and Young Adults. The chart on page 13 offers several structures that can help you engage in this collaborative approach.

In addition to the “how” of gathering student voice, the “who” is just as important. Typically, when we seek student input, the scope and perspective are often limited to students who are highly engaged and high achieving—those who are perceived by teachers and administrators to be student leaders, and therefore their opinions are more likely to be valued. Schools willing to convene diverse groupings of students—not just the high achievers—to discuss critical issues often find that students can make insightful and valuable contributions to the collective perspective. We have found the intentional gathering of student voice is an essential and strategic step in the transformational work of becoming a school focused on building relationships, cultivating hope, and fostering the development of the whole child.

When students are asked about the importance of gathering student voice, they give us compelling reasons. “It makes us feel heard, safe, relieved, worth it, cared for, smart, acknowledged, trusted, wanted, validated, and understood. Because you give me an opportunity to tell you the truth, it makes me feel like I can trust our school,” note students who were part of the 2018–20 focus groups.

What We Learned From Students

When we took a close look at these student comments, we found commonalities across school systems that can be instructive for all. The focus was on how the schools could support students’ academic and personal success when confronting barriers such as substance use, grief, sexual identity, and parental incarceration. When students’ lives were complicated because of these potential barriers to their success in school, there were three trends across the nine schools:

- Students want to learn and interact in a space that is responsive, not reactive.

- Students want available and accessible resources that are discoverable, relatable, and relevant to overcoming the effects of barriers in their lives.

- Students want teachers and administrators to be compassionate and nonjudgmental.

Don’t React, Do Respond

Students in the focus groups noted that teachers’ judgment based on their perceptions of students and their families can damage the relationship between the student and teacher. For some students, “[sexuality] is not a choice, and, no, my sexuality doesn’t impact my grades, but the reaction to my sexuality can impact my learning in school” and other teens found it “almost impossible to find a place where there is no judgment when you are talking about your mom or dad being in jail.” What students request is “support instead of punishment.” Refraining from punishment and judgment while supporting students’ academic and personal success with services, support, and opportunity is the first duty of implementing wraparound services.

Providing Relatable Information, Experienced Mentors, and Support

One of our goals as educators is to create an environment that fosters student academic and personal success. Sometimes this means improved curriculum that is relevant and current, which could be substance abuse prevention information in the lower grades, or the ability to meet with young adults in recovery to discuss substance use and sober living on college campuses, in the workforce, or in the military. In addition to instruction, students who were part of substance use focus groups called support groups: “a mentor, and meeting and making friends with other students who are going through the same thing.

Additionally, students want “someone who is trained to listen,” “role models [who] discourage us from using,” and “people available who have shared the same experience.” Grieving students suggest educators and other adults “share experiences about when [they] lost somebody, and how [they] got through it,” and “activities to honor someone I’ve lost.” They list things like remembrance activities, therapy, one-to-one counseling, and animal therapy that would be helpful. Students confronting complex issues recommend the use of advocacy groups that promoted assertiveness, self-esteem, positive body image, and empowerment with “open and louder support from staff.”

By freeing students from punishment and judgment and providing them with mentors and structured support activities, the final task in implementing wraparound services involves school officials taking empathetic measures. One student said it quite well: “I wish those who love, support, and encourage us could understand how important their support is to us.”

Taking Action

When a school seeks to support the development of the whole child, they must create relevant and responsive services that are focused and informed by students. Schools that have involved students in program design related to student-identified barriers have launched innovative, impactful programming.

- One inner-city school started a grief support group, altered how they responded to student death(s), began hosting remembrance activities to heighten sensitivity to grieving students, and increased teacher education regarding the impact of a loss to a teen.

- Another school expanded its programming to build healthy relationships by partnering with public health programs to offer an after-school course focused on sexuality, sexual activity, and harm reduction. Students had to have parent permission to participate and be at least 16 years of age.

- Several schools have rewritten policies and offset suspension days for students participating in services such as anger management support groups, peer mediation and conflict resolution, or participating in mentoring sessions with an adult in recovery.

- One school committed to addressing substance use and recovery by introducing a recovery-informed prevention curriculum beginning in the elementary grades. The same school district incorporated the Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment tool as a universal screener in their health classes and partnered with their local college/university’s association for young adults in recovery.

- Some schools have responded to student requests for wellness programming and animal therapy by using therapy and service dogs in their counseling areas and adding yoga, meditation, and tai chi to their physical education options.

These are challenging times. To be certain, our students are facing all these realities as well. Still, there is cause for optimism and hope. Schools can be protective factors for children, and our students have the ability, insight, and creativity to help us navigate our path forward.

Leigh Colburn is co-founder of The Centergy Project and a former principal, educational consultant, and author. Taylor Norman is an assistant professor in the College of Education at Georgia Southern University in Statesboro, GA, and co-chair of the National Youth-at-Risk Conference. Alisa Leckie is the assistant dean for Partnerships and Outreach and an associate professor in the College of Education at Georgia Southern University. She is a co-chair of the National Youth-at-Risk Conference.

Sidebar: Building RanksTM Connections

Dimension: Student-Centeredness

Intentionally provide opportunities for student voice and leadership to shape decisions, such as through a student council, a seat on key leadership teams, or freedom to direct school projects and activities. Steps and additional actions to intentionally provide opportunities for student voice and leadership:

- Develop formal leadership opportunities for youth, such as student councils, student involvement teams, or student representatives on other committees that can have input into school decision making.

- Seek ways to acknowledge and empower informal leaders.

- Survey or conduct focus groups of students to determine whether their needs and interests are represented by the school’s academic and extracurricular offerings.

- Ensure that all students, not just expected student voices, are heard and participate in leadership roles.

Student-centeredness is part of the Building Culture domain of Building Ranks.