Preparing Tomorrow’s Principals Today

Being a principal can be a lonely and overwhelming task, and that sense of isolation is amplified in the first year. A 2018 report, “Principal Attrition and Mobility: Results From the 2016–2017 Principal Follow-up Survey,” conducted by the U.S. Department of Education, suggests nearly 1 in 5 schools have a different principal in one year than in the previous year, and approximately 10% of principals leave the profession annually. One reason for that turnover is lack of preparation for the principalship, note authors Stephanie Levin, Kathryn Bradley, and Caitlin Scott from the Learning Policy Institute in “Principal Turnover: Insights From Current Principals,” a brief published with support from NASSP.

We at Pitt County Schools in Greenville, NC, have developed a robust candidate pool through the development of an intentional principal pipeline.

Detailing the Process

Our district began by first clarifying the desired outcome. Knowing the struggles first-year principals face, we sought to invest in high-performing assistant principals (APs) whom we expected to move into the principalship within 18–24 months. We believed if we could transition them more effectively, they would be more likely to remain in the position and be successful in the long run. We did this by working with district leaders to answer the question: “What are the characteristics and competencies necessary in the first year of being a principal for success in our district?”

Investing the time to think deeply about this question and discover answers was a critical component to our success. Over the course of about two hours, the team engaged in rich dialogue regarding differences between first-year and experienced principals. For example, one person suggested a key competency of a seasoned principal was “attracts and retains talented teachers,” stating that a significant factor in principal success was recruiting and hiring the best teachers available. Another person suggested, however, that while recruitment might be a key aspect of success for experienced principals, many of our new principals begin their job less than a month prior to the opening of school when most classroom teaching positions have already been filled.

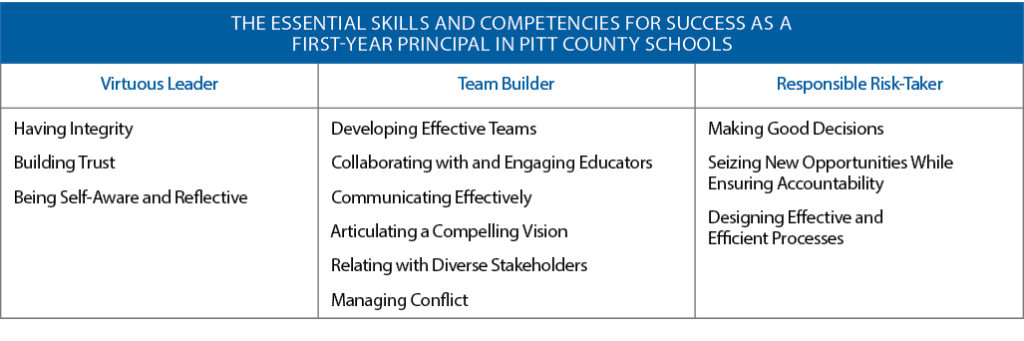

As the group continued to talk, they eventually prioritized “growing and developing teachers” as a core competency for first-year principals and moved “attracts and retains talented teachers” as a competency of experienced principals. With this insight, the training program for APs focused on developing congruent skills. Similar conversations occurred related to many other desired outcomes, and at the conclusion of the meeting, the group identified 12 essential competencies.

With those competencies in hand, the next question was, “Based on this list, who are we saying we want principals to be?” The answer to that question allowed us to categorize the competencies into three clusters: virtuous leader, team builder, and responsible risk-taker (see box below). With this framework established, we created a training program aligned to those goals: the Academy for Transformational School Leaders (ATSL).

The Program

Our ATSL includes a combination of group face-to-face trainings, virtual meetings, and ongoing individual coaching provided over 18 months. APs submit applications, which are reviewed by program directors. After an initial review, all applications are forwarded to district senior leaders—those who supervise and evaluate all principals—who then admit participants into the program. Upon acceptance, participants complete 8–10 days of training, plus additional coaching. Training topics include both off-the-shelf content provided through partnerships with external organizations and internally developed sessions. All topics are aligned to the skills and competencies senior leaders identified. We also provide opportunities for participants to interact with district leaders by hosting two luncheons for them with the superintendent and assistant superintendents.

Given that we started by identifying desired competencies, we intentionally focused ATSL on what Robert J. Anderson and William A. Adams refer to as the “inner” and “outer” game in their book, Mastering Leadership: An Integrated Framework for Breakthrough Performance and Extraordinary Business Results. The “outer game” describes the behaviors we exhibit; the “inner game” describes the underlying thoughts, motivations, beliefs, and values that an individual has—something that Tim Irwin calls one’s “leadership core” in his book, Impact: Great Leadership Changes Everything.

To support this effort, participants take three commercial assessments to support them in becoming more self-aware. Two of these are self-assessments and one is a 360-degree feedback instrument. The first self-assessment identifies preferred personality tendencies, while the second measures emotional intelligence. The third assessment provides an opportunity for participants to receive feedback from evaluators on their leadership behaviors and is delivered near the end of the program after they have had opportunities to apply their learning from ATSL. During coaching sessions, APs explore what their results suggest about how their beliefs, values, and underlying mindsets contribute to the results they are getting. In short, they identify the “inner game” driving “the outer game.”

Sharing Impact

Now in its third cohort, initial impact data is available for the program. Overall, when district leaders were asked how the quality of principal candidates over the past two years compared to previous years, they overwhelmingly reported the candidate pool is stronger and APs are better prepared to navigate the transition to the principalship. Besides this generalized and anecdotal feedback from district senior staff, we also asked past participants who have successfully become principals to share their feedback and experiences. Overwhelmingly, participants reported the program helped them: (1) better relate to and with stakeholders, (2) understand themselves as leaders, and (3) manage competing natural tensions within organizations.

“To me, the most important element in my first year as principal was building relationships,” said Principal Dakota Franklin. “The ability to communicate, be transparent, and open was vital in my first year. Emotional intelligence is also important as you work to get to know your staff and understand your building.”

Another participant, Loretta Stevens, said, “I had a situation with a staff member who was disgruntled and tainting the school climate. [The skills from a particular training] were used to plan a meeting with her to correct behavior.”

These qualitative measures support the quantitative data showing we have surpassed program goals for AP advancement. Specifically, the program set a goal that 50% of graduates would be promoted within two years. In the first cohort, five of the seven participants (71%) were promoted to either a principal or district leader position within one year and a sixth participant was promoted to a principal position after two years. In the second cohort, two participants (25%) were promoted before the cohort even ended, and in the third cohort, two participants (40%) were promoted to either a principal or district coordinator position before the program ended. When we first developed the program, our goal was for 50% of participants to move into a principal or district leadership position within two years. We have met that goal.

Lessons Learned

Developing leaders takes time and ultimately begins by identifying the goal and answering the question, “Who do we want principals to be?” Knowing our goal was to help individuals become virtuous leaders, team builders, and responsible risk-takers provided us focus. We could determine which trainings or external partners to work with and which ones would not move us toward our goal.

A second critical lesson learned was the importance of individual coaching to complement the group sessions. Every participant was coached a minimum of one to two times each month. In these coaching sessions, APs developed their own plans to implement skills learned in group sessions and integrate results from the assessments. Ultimately, ongoing coaching allowed for and empowered sustained application in a way that group sessions did not.

Third, the simultaneous work on both “inner” and “outer” skills resulted in deep, transformational learning. Participants reported that many of the most impactful experiences happened when they learned more about themselves as individuals—e.g., personality styles, emotional intelligence, or becoming aware of the beliefs and assumptions that drove their behaviors. Additionally, alumni report that the skills and mindsets they learned have impacted them as much—if not more—in their home and personal lives just as they have empowered them as school leaders.

By valuing and focusing on the whole person rather than simply their job responsibilities, participants grew in both areas. This focus on “inner” and “outer” confirmed our supposition that leading others begins with leading oneself. “The Academy provided me with many opportunities for self-reflection and looking at my own characteristics and skills that I had,” Franklin says. “It helped me grow my skill set while allowing me to see skills and positives that could be beneficial in the role of principal.”

Strategies for Replication

Our primary recommendation for those looking to improve their principal candidate pool is to take the first step by answering the question, “Who do we want principals to be?” While we answered the question as a district, individual principals do not need to wait on the district but should answer it themselves so they can be intentional regarding the support they provide their APs. Similarly, recognizing that effective leaders have both an inner and outer game, individual principals and district teams can focus their support for current APs on helping them develop in both areas.

Finally, do not underestimate the necessity of ongoing, regularly scheduled, and targeted coaching. Again, this is something that can be provided by either district support personnel or principal-supervisors.

In a follow-up coaching meeting, an AP was asked about her responses to and thoughts about the session. Specifically, the AP was asked what stood out to her, what she wanted to implement, and how she wanted the lessons she learned in the training to influence how she showed up as a leader. The AP responded with several specifics regarding behaviors she wanted to see in herself and others. She then asked if we could come to her school and train her entire staff. As a trainer/coach, we always love to hear that people enjoy our sessions and find them valuable, especially when they encourage others to attend them or invite us to deliver the session to a new group.

However, our goal was not to train her school but to develop her, so rather than looking at the calendar to book a training, the coach responded with, “You obviously value the learning and want others to experience it. Before planning for someone to do that for you, what are some things you can do right now to bring about the changes in your teachers you want to see? What skills did you learn last week that might support you in that?” We then reviewed the resources from the training, identified some specific strategies to use, anticipated concerns, and came up with action steps for her to take to influence her teachers. As a result, she began to see herself as the initiator to bring about desired changes rather than waiting for us to do it for her.

She is a great example of a leader: someone who took initiative to positively influence others to improve the school together. And it came about through an intentional focus on both inner and outer skills; deep, reflective coaching resulting in increased self-awareness; a combination of group and individualized learning; and a coach willing to challenge her initial thinking. Those can all be provided by individual principals for their APs as much as they can be provided by a district training program.

The only way to change the future is to change how we are operating in the present. Perhaps the best thing district and school leaders can do to grow future school leaders for tomorrow is to invest time and resources in developing their own self-awareness and skill as a coach today.

Thomas R. Feller Jr. is the director of professional learning and leadership development at Pitt County Schools in Greenville, NC. Seth N. Brown is the director of educator support and leadership development at Pitt County Schools.