Roundtable: Leading and Educating in the era of ChatGPT

Principal, Upper St. Clair High School

Principal, Highlands Ranch High School

Principal, Wheeler High School/Wheeler Middle School

As school communities grapple with the power of AI, how are principals educating themselves, their students, and their staff members about language-processing tools and their various uses? To find out, Principal Leadership contacted Kristen St. Germain, the principal of Wheeler High School/Wheeler Middle School in North Stonington, CT, and the 2023 Connecticut Principal of the Year; Christopher Page, EdD, the principal of Highlands Ranch High School in Highlands Ranch, CO, and the 2023 Colorado Principal of the Year; and Timothy Wagner, EdD, the principal of Upper St. Clair High School in Pittsburgh, PA, and the 2023 Pennsylvania Principal of the Year.

Principal Leadership: How are you as a principal educating your staff and students about AI in school?

St. Germain: The first thing our district is trying to do is change the perception that AI is going to get rid of all of us. I think that’s where teachers have this fear, “Are you going to need me in 10 years if this is what’s being created?” Our superintendent is new, and he tied this into his second-year goal of innovative instruction. At convocation, he did this thing with AI where he showed us a video of himself at a local grocery store, and he walked up to one of those robots that follow you around the store and said to it, “Hey, can you help me find celery?” It didn’t do anything. And that was his point. Technology is great as an enhancement, but it is never going to be able to offer the human element that as educators we bring to the table each day.

PHOTO COURTESY OF KRISTEN ST. GERMAIN

Page: We looked at a lot of things Kristen talked about, such as educating our staff and making them feel more comfortable with it. When faculty members in our English department brought up that a couple students had plagiarized, that started us down the road of ChatGPT. We did a training session with our entire staff on the use of it not just to detect plagiarism but ways we can weave it into our classroom. For example, one teacher has an AP exam written by one of her former students who scored a 5 and a ChatGPT version that would probably be a 5 and she puts them both in front of students and she has them work through it from the standpoint of “You’re going out into the world and you’re going to have to decipher some of this so can you tell what’s been AI generated and what’s been generated by a person?” I tell colleagues and students that last year, we had an applicant for a job here, and in their cover letter they had “insert school here” in two places. They didn’t understand why they weren’t getting interviews. They reached out and said, “I’ve applied to 25 different places, and no one is giving me an interview.” I got to be the bearer of bad news, and I explained the issue. I think that story holds lessons for us all. In terms of assessing student learning, our staff has also discussed how it’s perfectly all right to go back to the days of handwritten first drafts, and teaching kids to take their time to write out their ideas thoughtfully and then be able to see that transition and growth in their writing and then go from writing to typing.

Wagner: We’ve tried to educate staff in both informal and formal ways. We’ve hosted some optional teacher focus groups where staff can come together to talk about this topic. For example, they might share an article they found. At the start of the school year, we did some formal professional development and encouraged everyone to at least create an account, get in there, and design a lesson plan using some prompts. We wanted teachers to see how to use it for their benefit. For students so far, our education around AI hasn’t been too broad. We’ve updated some of our library resources and some of the ways that our citation guides are structured. We’re eventually going to have pilot groups of students use some of the tools and then give us feedback before we roll anything out widescale.

Principal Leadership: Are there specific guidelines around ChatGPT that exist yet in your districts?

Page: There’s not an official policy. For the most part, the usage that we’re seeing out of AI is around plagiarism and we already have a lot of policies around how that’s handled. If anything, we’re trying to show grace because when new technology ever comes out there’s sort of this experimental window period where you’re trying to work with students and families. You’ve got some families that say, “This is what their world is going to be so why would you punish them for using it?” We have likened it a lot to cell phones. When cell phones were first coming into the classroom, it was easy to say, “Do not use cell phones at school, do not have them on, put them away, no way at all.” Then, we as educators started learning how to use cell phones in instruction in effective ways because it’s the world’s greatest encyclopedia right there in your pocket. We have found ways to embrace it but not let it take over the classroom.

The first thing our district is trying to do is change the perception that AI is going to get rid of all of us. I think that’s where teachers have this fear, ‘Are you going to need me in 10 years if this is what’s being created?’

—Kristen St. Germain

St. Germain: Like every other advancement in technology, it’s about teaching students and staff proper use. We can’t bury our heads in the sand and say no to AI in our schools—that is just a recipe for failure. Policies must be put in place and current ones in place need to be updated and reviewed to fit these technological advancements as they impact our schools. I also think it’s more important that as educators we know what the ins and outs are before we start exploring AI with our students.

PHOTO COURTESY OF CHRISTOPHER PAGE

Wagner: In our professional development around AI, we categorize AI into three lanes, and we always identify for teachers what we’re talking about. One of our lanes is how you can use AI behind the scenes. Another lane is how does AI show up in your classroom and how do you invite students to use it? And the last lane is how will I catch plagiarism? At times, the conversation pulls back to the scary parts of it, but by creating these buckets we help teachers stay focused on what it is we are trying to work through together.

Principal Leadership: Can you share any examples of students and staff using AI in your school?

Wagner: Assessment is one example. We’ve had bigger conversations about mastery learning and students’ ability to retake assessments to demonstrate their learning. Sometimes the roadblock to that was the number of versions of tests teachers would have to create to assess students a third or fourth time. We have found that AI is a way that some of our teachers have been able to continue to assess towards mastery as a result of generating problems of similar complexity to the ones that were on the original test. Another thing that’s really helped in terms of staff use of AI is that we moved a couple years ago from a 50-minute class period to an 80-minute class period. Some teachers were excited about moving to a block where they would be with students three times a week but for longer chunks of time. But staff who didn’t really have a great idea about how to conceptualize that block have used AI to generate lesson designs that meet that number of minutes with variety and hands-on-learning activities. It’s been a nice tool for teachers who maybe weren’t quite sure how to plan such lessons.

St. Germain: I lead a 7–12 school, so we’ve been working with our middle school teachers on making sure they’re building in activities like interdisciplinary units to bring students together to practice important social skills that lately have been tested due to the pandemic and the increase of technology in their lives. At the beginning of the school year, my assistant principal and I held a meeting with our middle school teachers where we used ChatGPT to create a unit based on very specific prompters. What was awesome about it was that it made some very clever units filled with creative instructional strategies and activities and at the same time, we showed them how ChatGPT can be used to enhance their own teaching. We put the first prompt in, and we let it spit out lessons on fairs and another on ice cream. These were activities that we wanted to have our kids easily connect to. As we explored this technology, we realized there were some great ones that came up and there were also some not-so-great ones. We kept at it and made our prompts more specific. By the end of this session, we created two units that offered activities for all levels of learners. The activity modeled for teachers what they can do with this technology, and it underscored the importance of looking at the lessons as humans and deciding what to change. It also showed them that this is a great resource that can help with their instruction.

I’m encouraged by the fact that our community of educators is talking about tech in appropriate ways and finding those avenues and lanes for people to use it.

—Christopher Page

Page: With ChatGPT, you can type in parameters, such as, “I want this to be written like an eighth grader,” or, “I want this to be written like a junior in high school,” and so on and so forth. We often use AI tracker to see whether a student has used AI. What’s interesting is educating parents. That’s been tough because when you tell a parent your child has been caught through the AI tracker, they sometimes don’t believe it. They’re like, “I know my kid. My kid’s a great writer, I’ve seen their writing. They get As in English. There’s no way that they did it.” We actually have to sit down with them and show them how AI tracker works and how ChatGPT works, and they see just how quickly the words are written. It can tell you this entire paragraph was written in 45 seconds, or this entire page was written in one minute. Then parents suddenly understand. It’s been tough because we don’t want to lose trust with our community. You don’t want families to feel like you’re out to get the kids. But on the flip side you have to educate them alongside staff and students so that everyone knows what this new world is we’re walking into.

Principal Leadership: Have you as a school leader used AI in any of your work?

Wagner: Some of the time-saving things absolutely have been helpful for us. For back to school, we had a few professional development days in a row, and we were able to bring some variety to that which was helpful to our team. For instance, we used AI tools to create activities for staff to engage in as part of break-out groups or whole-group work. But then the added benefit was that we were able to say to staff, “Hey, guess what? We used AI tools to generate these activities.” We modeled the use and showed how it allowed us to keep things fresh.

Page: For spirit week, one of the things we do every year is a scavenger hunt. The kids really love it. I hide a golden egg on campus, and I don’t tell anybody where I’ve hidden it. Every year, I write clues in rhyme. Whichever grade finds the eggs gets more points. This year, I decided to use ChatGPT to write all of our clues. I fed it into the system and just flowered it up a bit more. That’s been a positive where we’ve been able to embrace it and add a little more element of fun.

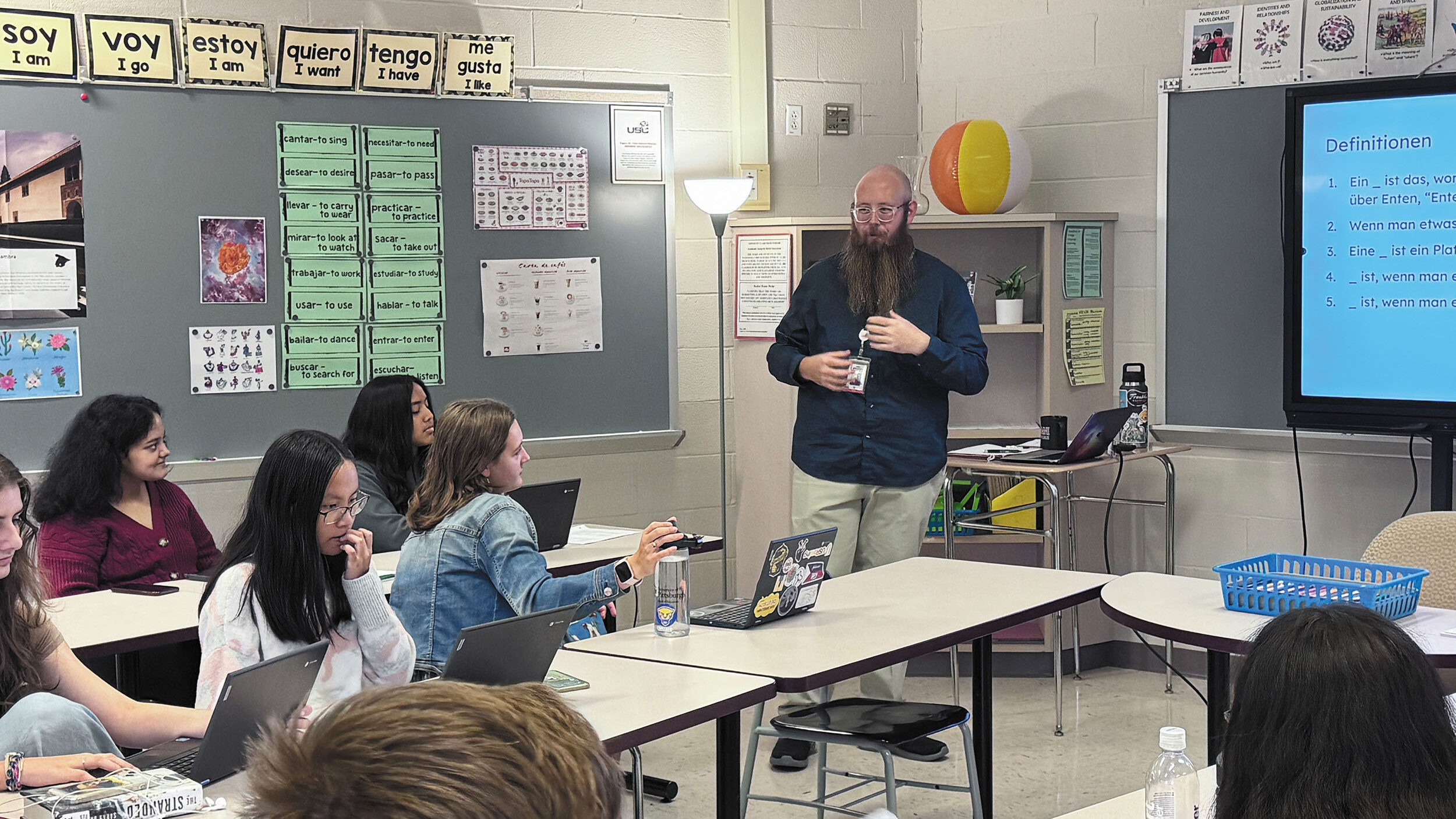

PHOTO COURTESY OF TIMOTHY WAGNER

St. Germain: Sometimes as a principal it’s easy to get stuck on time-consuming tasks, like drafting procedural letters or PowerPoint presentations. Although I know what I want in these items, sometimes I’m spending too much time making them perfect, or more animated, or simply making them look good for my audience. By using AI, my time to complete these tasks is quicker, and now my time can be better spent elsewhere. There are some amazing AI programs out there that you can just take your information and within 35 seconds it spits back at you this awesome presentation. You still do the leg work, and you still have the ability to make it personal and yours, but it can save hours of your time. For me, it’s about finding ways to use AI to allow us to be where we want to be, to do what we want to do that’s most effective for our staff and students.

Principal Leadership: As educators what are your feelings about this new technology?

St. Germain: I’m excited about it. It’s not just for students but can help enhance our instruction as educators in the classroom. There’s equal opportunity for everybody in the building to really be better because of this type of technology. My goal is to get my staff to explore it a bit and find ways to introduce it to them. I’m a little wary because of the financial piece of it. Are we going to be able to use these great programs if they’re not free anymore, and how will they impact our budgets that are already tight if we have to pay for it? Will we be able to sustain this movement, especially if we get everybody so excited about something at this initial level? It’s hard sometimes with budgets and the financial climate we’re in to imagine how we will fund such advancements. I am worried about how to sustain it once we’re hooked on it.

AI is a way that some of our teachers have been able to continue to assess towards mastery as a result of generating problems of similar complexity to the ones that were on the original test.

—Timothy Wagner

Wagner: Part of the hard work of being a leader is you have to integrate all the feelings and empathize. But for me, it’s optimism and excitement because this technology is forcing us to answer this question: When we have children in our presence, what matters most? What are we actually doing with the time we have students in our classrooms versus what will homework transform into as a result of this tool? It’s really pushing us into a back-to-basics conversation around strong instructional strategies and sound assessment. Years from now, another new tech tool will again prompt some of these same important conversations.

Page: Tim is spot on. As leaders, we become enthusiastic about the things that help our teachers and kids learn and try to help them embrace that. We are able to be empathetic to the fear and some of the frustrations that come with it. In general, I’m encouraged by the fact that our community of educators is talking about tech in appropriate ways and finding those avenues and lanes for people to use it. At the end of the day, we’ll evolve because that’s what education is all about.