Leading for College and Career Access

One of the most difficult tasks as a leader is guiding a school through a change that requires involvement from everyone, yet no one feels is their primary responsibility. In our experience, college and career access is one of these issues. While postsecondary preparation is embedded in many high schools’ mission statements, no one apart from school counselors has it listed in their official job description. Yet providing all students with the information and individualized support they need to find and pursue a postsecondary path is something that requires a full-school effort.

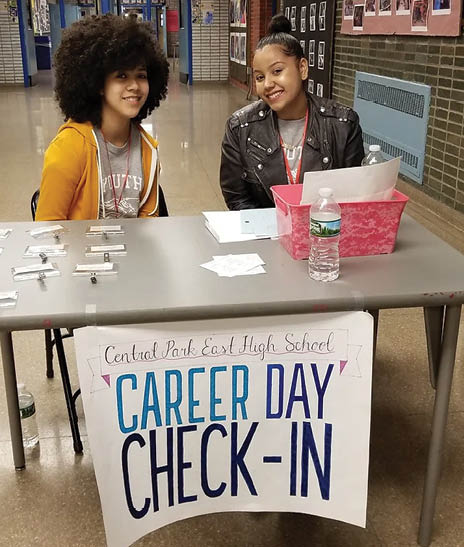

In our work—as the principal of Central Park East High School in New York City and as a staff member of College Access: Research & Action (CARA), an organization that coaches leaders through comprehensive development of postsecondary access programming—we have found time and again that a program never fully takes hold unless it has the committed guidance of a skilled leader. So, building on our 2020 policy report in this area, over the last year we worked with a group of experienced principals to document leadership strategies that are essential to catalyzing this kind of change.

Our work focuses on schools where a majority of students are the first in their families to attend college. These students are 21 percentage points less likely to enroll in college than those whose parents have bachelor’s degrees. Because their families have often not been afforded the knowledge and resources to navigate this process, schools striving for equity must create the infrastructure for all students to do their entire college and career process within the school day. This approach is encapsulated by three tenets:

- It must be an entitlement for all, not a privilege for some. Every student should be able to meet a trained counselor one on one in 11th and 12th grades to explore postsecondary options and receive personalized support.

- It must be approached as an instructional area with space in the school’s curriculum. Exposure to the landscape of college and career options, the application process, and financial aid must be integrated into the school day from grades 9–12.

- It needs to be everyone’s responsibility. The full staff should be trained and enlisted to support postsecondary work so that students have greater access to trusted adults with accurate, culturally relevant information.

Implementing such a comprehensive program is not easy. To that end, the principals we worked with shared six strategies they’ve used to make this change stick.

1. Identify a champion for postsecondary access.

The first step in this process is marshaling the knowledge and time to lead this work. Most principals aren’t taught about postsecondary access in their leadership programs, and while all teachers went to college, most only can speak about their particular experience, which is probably out of date. Yet, as one principal told us, “To strategize and lead this work, you need to have a balcony view of what’s happening in the college and career process.” You must know, for example, what the FAFSA application looks like, when deadlines are, and how to counsel a student through this journey. This means that leaders usually need to invest substantial time, as author Michael Fullan says, to “participate as learners” in the work.

In our experience, at small high schools either a principal or assistant principal can do this. But at large schools, an assistant principal who is given sufficient discretion is almost always a better fit because of the level of detail needed. Many schools consider making a college counselor the project leader, but we have found counselors usually lack the necessary decision-making power (e.g., shifting school schedules or adding programming) to lead this change.

2. Create a program instead of relying on one person.

For schoolwide initiatives like postsecondary access that fall outside staff’s primary responsibilities, it’s essential to create schoolwide infrastructure that organizes and distributes the work. Two common mistakes we see are assuming you can “outsource the problem” by expecting an outside organization to do all the work or by putting the entire postsecondary program on the plate of one counselor. Both of these make a school precariously overdependent on a single entity. Instead, the objective is creating postsecondary access infrastructure within the school, which means curricula and resources are formalized and accessible, multiple people have the knowledge to run the program, any outside organizations are consciously integrated into the work, and there is a culture of postsecondary support distributed across the school. As one teacher told us: “It’s not a one-person show—it relies on all of us.”

A key part of developing this infrastructure is creating a leadership team and regular meeting structures to guide the work. At a minimum, the team should include the school leader, the college counselor(s), and any teachers who will be program leads, though exactly who to include depends on the school structure and postsecondary program. Given the newness and time-intensiveness of this work, it’s critical that members of this core team are given ample time and support. And, as the program develops, strategic leaders will create support for when key staff people leave by building a deep “bench” of staff members who are experienced in this area and by constructing systems to ensure curricula, data, and processes are well documented and shared.

3. Articulate a vision worth working toward.

In addition to the core leadership team, there must be schoolwide buy-in for this work. To build this support, a leader can provide a vision for the school that helps staff members see how their work connects to the larger goal of supporting students’ livelihoods after graduation. In the words of one assistant principal:

“When you go to college and become a teacher, you are caught in this idea of specialization—you go into math if you want to teach math—but then everyone forgets what the goal is. What is the goal of high school? We’re working toward making sure our students have a successful transition to the next stage in their life. When people understand what they are doing is part of that transition, they become willing to step up and work toward that.”

Successfully articulating this vision requires conscious and consistent messaging. Part of this comes from offering schoolwide professional development on the postsecondary program and what all teachers are expected to contribute to it; for example, one principal included at least some aspect of college and career access in every schoolwide professional development day. Schoolwide rituals are also important. One school has a yearly “Preparing for the Future Day,” where younger students take the PSAT and older students begin their college applications, supported by the full school staff. Other schools have college decision days and alumni homecoming days. As author Paul Bambrick-Santoyo writes, these events provide opportunities to “create peak moments” and “narrate the positive,” which build a positive atmosphere and inspire future work.

4. Follow strengths and secure small wins.

For key decisions about the postsecondary program, such as where the college and career curriculum should be taught and where to begin program implementation, the advice we consistently hear is to follow strengths and secure small wins.

Time is a school’s scarcest resource, so the decision of where to teach the college and career curriculum is one of the most important a leader will make. As CARA’s 2020 policy brief details, there are pros and cons of four common instructional spaces—advisory, a subject class, a separate class, and special events—but, ultimately, making the best choice depends on knowing your school context and following your school’s strengths. As one principal told us, “Rather than plug holes, start with an assessment of your strengths.” This principal organized her school’s postsecondary work around special events, which thrived because it leveraged the school’s tradition of community learning days.

Similarly, principals recommended taking small steps that build momentum. While a postsecondary program should eventually span grades 9–12, it’s simply too big a lift to begin with every grade at once. In practice, this often means strategically prioritizing low-hanging fruit. For example, one school had a strong 12th-grade program and wanted to add a ninth-grade course, but when an 11th-grade elective teacher abruptly left, leadership used that opening to add a college and career class in junior year instead, which was a great success and generated enthusiasm for the ninth-grade class the following year. By following strengths, aiming for small wins, and being nimble when opportunities arise, you increase your chances of building momentum.

5. Connect the dots: data points and human voices.

A key part of leading for change is triangulating between data, staff, and students. Doing so provides a holistic picture of a program’s progress while building trust and accountability. Strong postsecondary access leaders track key quantitative data points, including applications, FAFSA completions, postsecondary enrollments (by college/program type), and college persistence. They also break down data by subgroup to check for disparities by income, race/ethnicity, English learner status, and students with IEPs.

In addition to numbers, it’s essential to observe and get feedback from teachers and counselors to see what’s going well and where they need support. Finally, speaking with students keeps leaders grounded in the ultimate goal: ensuring students have what they need to explore and pursue postsecondary options. Students are often the first ones to notice information that’s out of date, and they give candid accounts of what is and isn’t working. Connecting staff, students, and data helps everyone stay aligned with program goals and, as authors Shane Safir and Jamila Dugan suggest, this creates a school culture that prioritizes equity by valuing perspectives that are often overlooked.

6. Call in the community.

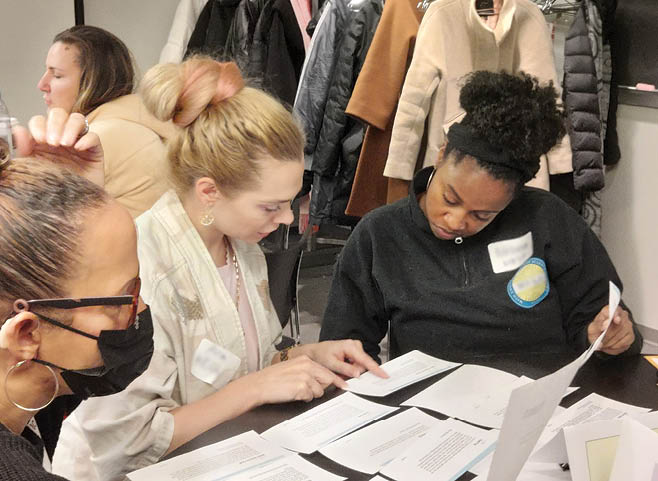

While it is critical to build the expertise and capacity to do this work in-house, schools can also strategically leverage community resources to expand their impact. Leading for change involves learning what staff lack the capacity to do and then finding partners who can provide support that integrates with the school’s program. Three ways of doing this include partnering with community-based organizations (CBOs), empowering students as leaders, and involving families.

CBOs—from college and career access specialists to youth development and community empowerment organizations—can provide valuable supplemental expertise and capacity; the key is finding partners that align with and support the school’s core program. CBOs are especially useful for providing additional counseling in areas that require specialized knowledge, like translating financial aid resources, advising students who are undocumented, and pursuing competitive scholarship programs.

Another way to build the strength of a school’s community is to leverage students. All of CARA’s programs use a peer-to-peer approach where students are trained in postsecondary access and are paid to assist counselors by helping other students create college lists, complete applications, and apply for financial aid. Empowering students to work with their peers also helps create a positive school culture around college access.

Finally, students’ families are an often-overlooked resource. We’ve found that involving families follows the same tenets as involving students: making support accessible to all families (e.g., available at different times of day and in multiple languages), developing families’ knowledge by engaging them from the ninth grade on, and dedicating resources toward individualized support. Finally, facilitating conversations between students and their families can help build shared buy-in to a student’s postsecondary plan.

Preparing for Change

The postsecondary landscape is entering a period of seismic change, with college enrollments declining and the world of work shifting. To help young people navigate these changes, schools will need to help them make informed decisions about their college and career paths. While this may seem like a lot to ask of educators as schools emerge from the pandemic, by using these strategies, leaders can create a postsecondary program that inspires school staff and prepares students for the new world ahead.

Reid Higginson, PhD, is the director of policy research at College Access: Research & Action (CARA), where he studies postsecondary access, college persistence, and peer-to-peer advising programs. Bennett Lieberman is the principal of Jackson Hole High School in Jackson, WY. Previously, he was the principal of Central Park East High School in New York, NY, for 18 years.

References

Bambrick-Santoyo, P. (2018). Leverage leadership 2.0: A practical guide to building exceptional schools. Jossey-Bass.

Bloom, J. (2020). Organizing for access: Building high school capacity to support students’ post-secondary pathways. CARA: College Access: Research & Action. caranyc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/2021CARAPolicy_V1.pdf

Cahalan, M. W., Addison, M., Brunt, N., Patel, P. R., Vaughan III, T., Genao, A., & Perna, L. W. (2022). Indicators of higher education equity in the United States: 2022 historical trend report. The Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education. pellinstitute.org/pell-institute-publications

Fullan, M. (2011). Change leader: Learning to do what matters most. Wiley.

Safir, S., & Dugan, J. (2021). Street data: A next-generation model for equity, pedagogy, and school transformation. Corwin Press.