Viewpoint: May 2021

SPONSORED CONTENT

Students want to come back to school—to see their friends.

But after they see their friends, how long will they want to submit to a structure that they have not had for a year and a half? Getting up at 7:00 a.m., classes that last 45 or 90 minutes, three-minute passing periods between classes, sitting in a seat with no food or drink allowed in class, and no access to social media? And what about handing in work and handing it in on time? Currently, schools are only getting homework or classwork from about 40%–50% of the students, and when they do get work, it is often late. There are a lot of A’s and F’s; some students are not getting any work, some teachers are giving A’s on the basis of completion, cheating is widespread, and some teachers are finding any way—including giving undeserved A’s—to encourage the student. How do you reintroduce rigor when there has been very little for a year and a half? Why would students come to school all day when many have learned that at home, schooling virtually, they can get all their work done by noon?

At the middle level, many teachers may not have met their incoming sixth graders in person, nor their incoming seventh graders, and they may only have limited time in person with their eighth graders. In high school, that covers half of the student population. How do teachers put structures in place when they have met fewer than a third to half of their students in person? Will the parents who work two jobs—who have come to rely upon their secondary school-aged children for childcare—want them to go back in person when they can be schooled virtually? How will schools find and reinvolve the approximately 20% of students who either cannot be found or do not engage at all?

There is, of course, the mental health challenge as well. Social isolation is as damaging to longevity as smoking. And for adolescents, their brain development is dependent upon peer interaction. How will we provide emotional and mental wellness support?

Keep Students Coming Back

Key motivators for students to come back in person (and to keep coming back) include:

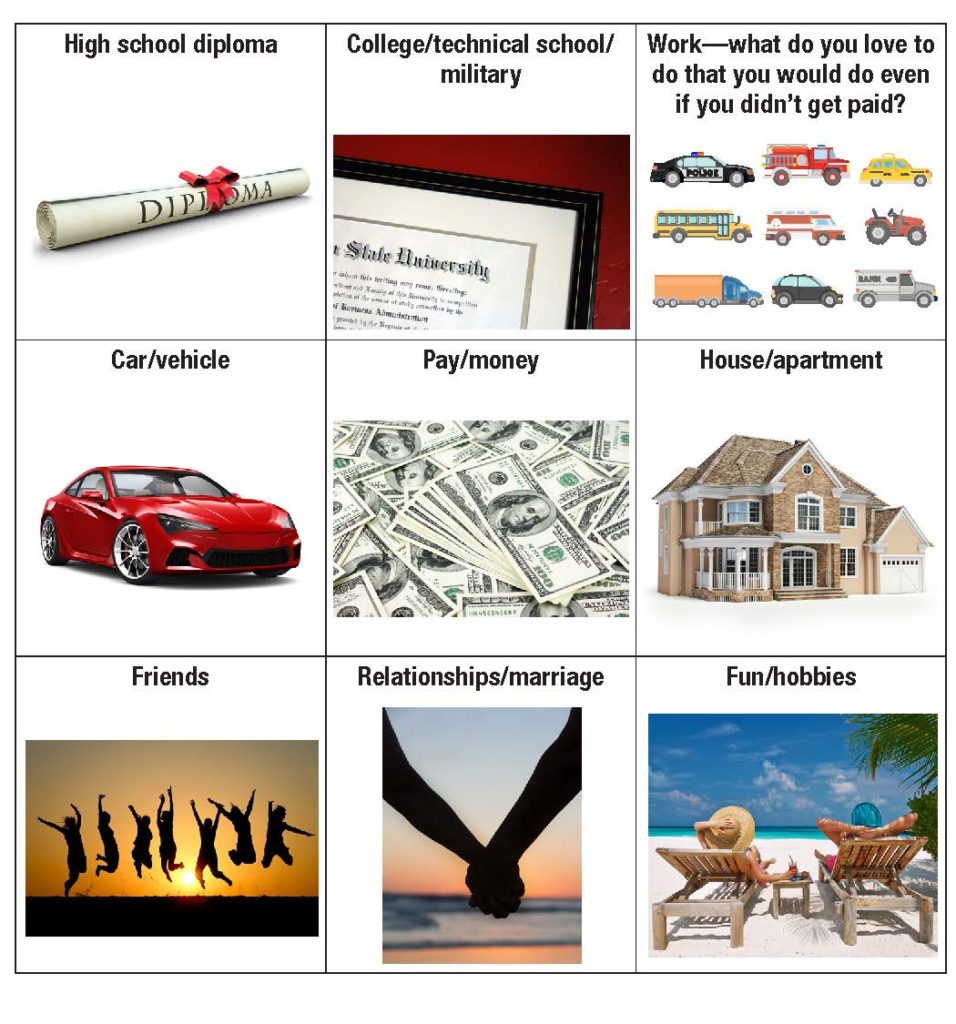

1. A future story. A future story is pivotal for a long-term commitment. In the research on resilience, focusing on the future is important. I like the visual storyboard—nine square boxes in which the key questions are: What do you want to have, be, or do by the time you are 25? What is your plan to reach that? How do your classes right now help you get there? Students select one image for each of these areas. Then they make a plan about what they will need to do to make that story a reality.

2. Opportunities for social relationships/belonging. I know one high school principal who did the following: She shaved a couple of minutes off each class. After first period, there was a 20-minute socialization time when students could be on their cellphones, talking, and eating. Clubs could meet, etc. Each student got this time if their attendance was at a certain level, tardies were minimal, and grades were passing.

3. Develop key relationships. Each student should have a key relationship with an adult on staff who makes daily contact and does not give up on them. Two questions you can ask students are: Who cares the most about you, and who do you care the most about? What you are listening for is an adult mentor. If they do not have an adult mentor, find a staff member who talks to them one-on-one every day for three to four minutes.

4. Access support systems. Help students access the support systems in the school and community that can help them work through, address, and acknowledge the realities in their lives—mobility, homelessness, abuse, and emotional and mental health issues. Many times, a referral system and links are needed to help with issues outside of school that destabilize school success. Make a list of these available to every staff member as well as the referral system in the school.

Getting secondary students to come to school in person and stay in school will be one of the biggest challenges of the 2021–22 school year.

Ruby K. Payne, PhD, is the founder and CEO of aha! Process Inc. She is also the author of Emotional Poverty in All Demographics: How to Reduce Anger, Anxiety, and Violence in the Classroom.