Roundtable: Innovation in Education

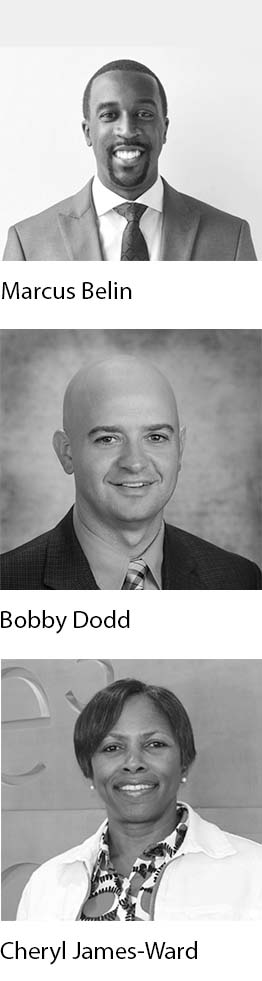

Thirty years ago, students spent their classroom time primarily listening to lectures, reviewing homework, and completing tests and quizzes as assigned. Few had opportunities to engage in project-based learning, and “innovation” was not a word normally associated with schooling. Since then, the educational landscape has changed, with educators seeking to stimulate students’ curiosity with innovative ideas for teaching and learning. To learn how school leaders are implementing such ideas, we interviewed Marcus Belin, principal at Huntley High School in Huntley, IL; Bobby Dodd, principal at William Mason High School in Mason, OH; and Cheryl James-Ward, principal and CEO of e3 Civic High School, a public charter high school in San Diego, CA. Principal Leadership senior editor Christine Savicky moderated the discussion.

What does innovation in education mean to you?

James-Ward: Innovation in education means preparing kids for a world that we cannot yet imagine—preparing them not only with the fundamental skills of reading and writing, but to be lifelong learners with the social and emotional skills to thrive and to help others thrive. It means preparing them to be flexible, critical, and creative thinkers. At my school, e3 Civic High School [e3], we do this with a focus on the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD] skills for 2030. We know that the future will require professionals to work in concert with artificial intelligence, with big data, with other cultures and nations different from our own, and even—in the near future—with quantum computers.

So, the focus, therefore, is on the human capacity for growth, change, and contribution to humanity. Innovation in education also means keeping a keen eye on the internet of things [IoT], innovative companies, and exchange-traded fund [ETF] companies. The ETFs that I’m talking about are on the stock exchange, and they invest in a diverse collection of securities. We keep a keen eye on ETFs like:

- Ark Invest in general technologies and Ark Genomic Revolution;

- Global X Telemedicine & Digital Health [EDOC], a teledoc company;

- First Trust NASDAQ Clean Edge Green Energy Index Fund [QCLN], a clean energy ETF; and

- Direxion Moonshot Innovators [MOON], a new-tech ETF.

We watch these ETFs in particular because they spend a great deal of money and resources tracking the most innovative companies in technology, social media, clean energy, genome sequencings, tech chips, and telemedicine. We believe that if we follow these ETFs, or ETFs like these, we’ll be able to track what’s happening and where to put our energy. We then share our findings with our scholars and staff through biweekly advisory check-ins, and we elicit their interest by tying it to the stock market.

Belin: Innovation in education for me, in the simplest terms, is encouraging our students and our teachers to explore what they’re learning by using different tools and technology, different means and ventures—whether it be data-driven innovation or student-driven transparency—then applying what they have learned. But most importantly, innovation allows our students and our staff to be risk-takers in a culture where we have become comfortable teaching and learning with what is given to us.

When we leave an idea open-ended or based within a particular problem that students need to solve, learning tends to come. But it also pushes students with the opportunity to understand that the sky’s the limit: Teachers can ask themselves, “How can I go deeper in my knowledge and become competent to not leave gaps in my students’ learning or understanding? Can I be innovative in the work that we’re doing?” Giving teachers specific resources that allow them to be disruptors in education allows our teachers to be able to open our classrooms to the world.

Dodd: Innovation in education for me is really looking at two things: student voice and teacher voice. What we try to do at Mason High School [MHS] is let our students drive our curriculum and our extracurriculars. We also give our teachers a lot of voice when it comes to how they teach. While we focus on personalized learning a lot, we also like our teachers to let us know what they need for their professional growth. And really, if you think about education, at least when I was in school years ago, neither one of those things existed. There wasn’t much student voice. As a student, you were told what you were going to learn and did what you were told to do. The same holds true for teachers. So, to me, that’s innovative in how we try to do things at MHS. We get student and teacher voice together and let them create great things.

What’s the most innovative program that you’ve ever seen or heard of?

Belin: In terms of some of the work that we are doing, it’s the robotics programs. Project Lead The Way—a program that a lot of schools have turned to for technology and career and technology programs—allows students to create and build. I’ve seen this concept not only grow, but also open many doors for our students and staff to go in different directions. Gateway To Technology is the middle school component where students go through the design and modeling process. They can conceptualize and figure out how to design and put ideas on paper. Then, across the course of the program, they can utilize their design and modeling process to think of typical, everyday tasks that need to be done and how these ideas can be applied to life. Students can physically build things or conceptually put things down on paper and bring them to life in a meaningful way, where they cannot only see their work and be proud of what they’ve been able to do, but problem-solve and become critical thinkers. The program also gives them the ability to see failure. Failure is a part of the process to success, and we can’t get to a successful end or a completion of something if we haven’t gone through iterations and failures and an understanding of how what we’re doing works.

Dodd: This idea is not from MHS, but one that I have seen in the state of Ohio, and I was blown away. At MHS, over 82% of our students go to four-year colleges. But that is not true for all of the schools in Ohio. They don’t have that same type of numbers or lineage, where families for years have gone to college. In eastern Ohio, Shenandoah High School partnered with other schools and created a program where students can get their CDL license on campus, so after high school they can land a job with it. We had never heard of a program like that where the school was using state money to create different types of degrees or certifications so their students could obtain their certification while in high school and immediately be qualified to obtain gainful employment. College isn’t for everybody, so we have to create options for students so they can go and be successful.

James-Ward: I would have to say Astra Nova, which is a school experience designed by Joshua Dahn (a friend of Elon Musk) to develop student voice and strategic thinking and collaborative problem-solving by putting teams of students together to solve complex games through gamification and synthesis. We have many students here at e3 who come to us three or four grade levels behind, so we can’t follow the exact practices of Astra Nova, but we can bring student voice and choice to e3 through design thinking. We believe that that is the next best thing to Astra Nova, and it provides our scholars with opportunities to focus on the fundamentals while also teaching them to solve complex problems they’re passionate about through the five phases of [design thinking], including discovery and empathy building, interpretation, ideation, experimentation, and evolution or iteration. That is part of what we believe to be the most innovative teaching practices.

What’s the most innovative teaching method that you’ve ever seen?

Dodd: My first principalship was at a little school called New Lexington in southeast Ohio. We worked along with two other schools to do college in the high school classes. Because we were so rural—Appalachia country—we used virtual technology to bring the college professor, who was nowhere near our town, into our classroom. We had three different high schools piping into the professor’s room, and the students could earn both high school and college credits.

It reminds me of this past year with COVID. We had many students who would get quarantined and be at home for two weeks, so our teachers utilized our resources and did some things that I just didn’t think were possible. Our quarantined students used FaceTime or Zoom to take part in AP Physics and AP Biology, and while they were not getting their hands on the experiment, their peers would walk them through and put the camera right down into the experiment. In the past five years we often said that we could do virtual learning if we had to, and then we had to, so we saw our idea come to life. I was very proud of our teachers last year, especially in those courses. We provided professional development for our teachers, but they walked through it themselves. They said, “We can make this happen. Let’s not let students fall behind,” and they did. They made it happen.

James-Ward: Design thinking, as I noted above, using TikTok. One of the things that was amazing to me was, as we talked about reimagining education, our kids noted that sometimes they can learn things in 60 seconds on TikTok that it takes us 84 minutes to do. So, I think TikTok can be a very innovative method not just for teachers to use, but also for kids to use for peer-to-peer instruction. Also, the use of virtual reality: We can’t always go everywhere, or buy all the resources that we need to do as many dissections as we need, or to visit other parts of the globe, but we can use virtual reality and Oculus headgear to bring the world to our students.

Belin: One of the things Huntley High School [HHS] has been using the past three years is a competency-based education format. It’s a small program within our building called Vanguard Vision, which allows our students to have a voice. Pacing is a little bit different than a traditional classroom, and our students are actually learning to master a competency as opposed to receiving a letter grade and being done. Teachers assess their content through performance assessments, which allows students to apply or show application of what they have learned to a particular competency. Students then get feedback on the content. This allows for students to engage in the content and apply their knowledge and for a teacher to assess them to make sure the students do not have gaps in their knowledge.

I use the example of flying a plane. You have three tests to take: the takeoff test, the flying test, and the landing test. If the pilot gets an A on the takeoff test, a B on the flying test, and then a D on the landing test, you’re not going to fly with that pilot because they don’t know how to land. The pilot has to go back and constantly do what they need to do to learn how to land a plane. For our students, it’s not receiving that B and saying, “OK; I’m good with that.” It’s allowing them to go back and say, “I haven’t yet met competency. I need to go back and take the feedback that my teacher gave me and do something different.”

Students can also incorporate their own interests on their performance assessment. The teacher is not just feeding them information. If the students can create it, their learning is accelerated. The last piece of this is pacing and student agency. Students own their work. Depending on how much motivation they have, they can move through a traditional course that may take eight to nine months to complete and be able to complete it in four or five months then move on to that next level. So, as a system, we don’t hold them back. We maximize the time they have by packing it in and knowing that they understand the content because of their level of competency and mastery.

If you could do anything to improve student performance in your school, what would it be?

James-Ward: This past spring, we spent about 30 hours reimagining high school education with scholars, our staff, our board members, and community members. With that, we’ve shortened the content standards and educational fundamentals part of the school day. We’ve gone from 84-minute periods to 60-minute periods for the first half of the day. Then we provide our students with more voice and choice in the afternoons to invest in their future through certificate programs offered through Coursera, Microsoft, and Google—that we pay for—by giving them opportunities to take additional concurrent classes at the community colleges. They leave our campus and go to the college campuses in the afternoon to take courses there.

To further explore workforce sectors, we spend a lot of time understanding the workforce with our students and teaching staff, and we allow our students to explore different career options. The afternoons provide students with time to meet with their design-thinking teams, to volunteer in the community, to give back through civic service and engagement, or to have more study time. That afternoon time is a 2.5-hour block where all of these things take place. We have invested in a number of computers—big gaming computers—to participate in club gaming. We’re part of the society of a national group of competitive gamers.

Belin: One of our biggest challenges, especially in our current world, is that there is a growing apathy for learning for our students because of the technology they have at their hands; they have become disconnected. They ask, “How does this apply to me?” And resolve, “I’m not going to do this. I’m going to just do the bare minimum to be able to get there.” That’s not all kids, but some.

Another area where we struggle is our SAT scores. Our SAT scores, coming out on the other side of this pandemic, have been low. Colleges and universities, especially some of these big-name colleges and universities, have eliminated the SAT requirement. So, what will they use to evaluate students? They will look at AP courses, and honors courses, experiences, and opportunities that students have had in high school, life skills, and habits of work life. They will take a holistic view of students. That’s an area where we can improve. But there will be colleges and universities that will use the SAT. So, we use a standardized test to make sure that we are meeting and exceeding in that area, but also focusing holistically on the child regardless of if they’re going to college, into the military, or straight into the workforce.

Dodd: When I look at improving student performance, it’s really improving teacher performance. We try to focus on our teachers really continuing to work and improve differentiation in how they offer things to students—all of our students—throughout the day. If I was to look at one area where we could increase student performance, it would be doing a better job professionally as educators in differentiating our practice and using our different structural methods.

If you could do anything to create a positive school culture in your school, what would it be?

Belin: There are many things we can do to create a positive school culture. It’s a lot because our demographic of students is always changing. Being in a four-year high school, my seniors don’t look like my freshmen, and my freshmen, when they become seniors, won’t look like my incoming freshmen; it’s constantly changing. In a post-pandemic mindset, I am being really intentional about changing the structures that normally exist within schools. I would love to have kids greeting each other at the door when they come in. I want to set up a system where students know they are seen and heard within the building, so we need to put equitable practices in place to allow that to happen.

One of the things that I’ve seen as an administrator is the diversity that’s happening, especially when it comes to gender, and students recognizing different lenses in which they see themselves and their lives. Recognizing special ed and disabilities, gender, diversity in color, ethnicity, and religion brings all of those pieces to where I want the walls of my school to look like a mirror—where kids can walk through the building and say, “Man, I see myself in the classroom. I see myself out on the sports field. I see myself in the cafeteria because I sit with this group of students, and we’re ‘the gamers,’ and this is what we like.” We need to elevate student voice, but also utilize and incorporate technology.

Some days our students just need to hear, “I love you. I care about you. We hear you. We see you.” But they also need to hear that from each other, especially within the spaces in which they spend most of their waking hours. Seven to eight hours of their days are spent in school, engaged in some type of social interaction, so we need to bolster the experience to make this the greatest four years that they have while we have them.

Dodd: At MHS, it’s really letting the students and teachers have the voice, as I said earlier, but then also, many schools collect data and surveys but then don’t really do anything with their findings. We focus on collecting that data, collecting that voice, but then actually seeing it through and implementing the ideas that result from them. We try to say “yes” all the time and let the students and the teachers create and build the clubs and organizations. We let teachers teach the ways they want to. That creates that positive vibe throughout the building, knowing that they can come to the administration, and the administration will support them.

I’m a firm believer that my staff and I are there to assist the students and the teachers to make dreams their reality. They don’t come to me for approval—they know they’re going to get a yes. I just have to figure out how I can make it happen for them. We have so many talented kids and teachers that sometimes it just blows my mind. My job is to make sure that if we’re going to have a positive culture, that I’m letting them do great things and not holding them back.

James-Ward: For us, it’s to continue to spend time understanding those we serve. Marcus mentioned that his seniors don’t look like his freshmen, so each year we’ve got to know who we serve. We spend a lot of time on cultural competence, and not just ethnicity but also gender and other communities. We visit the home of every freshman so that we understand them. I had a scholar who refused to work. He said, “This is not going to help me.” So, for us, it’s making sure that their time, which is their most precious commodity or gift, is used wisely—according to them, not me—and then we prepare them for a viable path and career.

We also focus on more choice and voice for our students through our afternoon reimagining education. We continue to use that competency-based grading and growth mindset that Marcus spoke of. We are a schoolwide competency-based school and have been for three years. Again, that started with a focus on growth mindset because we believe that kids don’t arrive at the same place at the same time, so we have to give them the space, time, and the support that they need to get there. We continue to focus on ensuring that every student finds their viable path and career that allows them to take care of themselves, their families, and to give back. And we note that once they do that, they are fully engaged because they know where they’re going and what they want to do. We also continue to live our motto: Take care of you, take care of each other, and take care of e3.

Why is innovation in education so important?

Dodd: It’s important because education’s not really traditionally the most innovative thing in the world. So, if we’re going to try to put learners out there—our kids who can do great things—we need to be innovative and keep changing so our kids can go out into a society where they can be the game changers that we need to keep growth going throughout the country and the world. It’s so important for us as leaders to continue to push innovation with our students and our families, because it is needed so much. Even small changes we make can create big, big waves in the future.

James-Ward: Innovation in education is important because we can’t prepare kids to work alongside artificial intelligence and quantum computers if we don’t prepare them to both understand the future, the technologies, and the innovations. We have to prepare them with the skill sets to work in concert with all of this.

Belin: We are preparing kids for jobs that don’t yet exist. We have to challenge our young people to become fearless learners—risk-takers. We can teach them leadership skills, teamwork, and collaboration, and strengthen their core. Their core of math, their reading—we can do all of that. That is our responsibility as educators. But when teaching them, we can’t say that we know it all. We have to give them tools so when they walk across that stage and then compete globally within the workforce or college, they’re prepared for the next level.

We must prepare them for what could possibly exist. Change is a constant every day, every hour, every minute, and every second. New things are being created and new ideas come to the table. With that changing dynamic in our life, what is and what will be for our kids is something that we have to prepare them to be able to do. We have to trust them and allow them to explore and give them access to the world that exists. Being innovative allows us to not stand still and continue to stagnate because this is what education has been. As school leaders—as educators—we have the ability and access to allow what we want to allow. We have to open up the doors and blow the hinges off and allow things to come and go as they do.