Role Call: February 2023

Children from an immigrant background are a growing population in U.S. schools with diverse characteristics, needs, and strengths. About 27% of school-aged children have at least one parent who is foreign-born, and 23% speak a language other than English at home. Students identified as English learners make up about 10% of the school population, with larger shares in elementary grades than secondary. All children, regardless of immigration status, have the right to enroll in public schools, and those schools have obligations to ensure English learners have meaningful educational opportunities.

Schools are often the first public institution that immigrant parents come in contact with, and their role in immigrant integration is critical. In addition to teaching children many skills they need to thrive, schools also serve as connection points to community resources for parents and families. Understanding immigrant families’ journeys, their needs and strengths, and what resources they have access to, can help school administrators offer a warm welcome and set children and families on a path to well-being and academic success.

Where Do Immigrants Live?

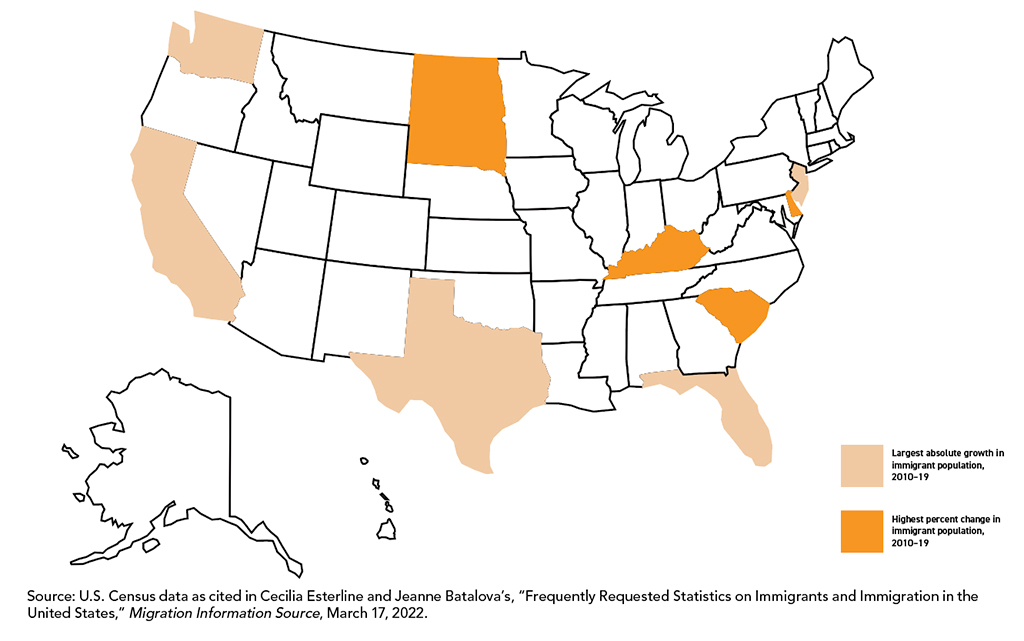

While large numbers of immigrants continue to settle in the traditional receiving states such as California and Texas, the states with the highest percent increase in immigrants over the 2010s were Delaware, Kentucky, North Dakota, South Carolina, and South Dakota (see map below).

In recent years, populations from Afghanistan, Ukraine, and the Central American countries of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras have been much in the news. While these newcomers are settling throughout the United States, many are likely to reunite with established communities such as Afghans in Sacramento, CA, and Fairfax County, VA; Central Americans in Los Angeles and Houston; and Ukrainians in Brooklyn, NY, and Chicago.

What Supports Are Available to Immigrant Families?

Immigration categories. Immigrants mainly come to the United States for humanitarian protection, economic opportunity, and/or family reunification. Individuals who have been persecuted or fear persecution based on their race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group can apply for protection as a refugee or asylee. Many immigrants, such as seasonal and agricultural workers, enter the country on a temporary employment-based visa, and others may qualify for a permanent employment-based visa. Such immigrants can generally bring their spouses and children with them; in some cases, their families join them later.

Some immigrants may be allowed to enter the country temporarily through parole because of an urgent humanitarian need, even if they do not meet the protection, employment, or other criteria needed for formal admission. Afghan and Ukrainian parolees are recent examples. Temporary Protected Status (TPS) is another flexible and short-term immigration benefit that the United States can offer people who are already in the country and cannot return home because of ongoing armed conflict, an epidemic, environmental disaster, or other special circumstance. Parole may be granted for up to 18 months and TPS is typically granted for 12 months or less, though both can be extended.

Unauthorized status and asylum seekers. Most immigrants are in the country legally. However, about 1 in 4 immigrants live in the United States without authorization, either because they entered illegally or overstayed the time frame specified for their visa, parole, TPS, or other immigration decision. Many live in fear of deportation and take steps to avoid encounters with government officials. These immigrant families may also be fearful of interacting with schools and may not know that school personnel are not involved in immigration enforcement. Some apply for asylum, including unaccompanied children who have crossed the southern border without a parent or legal guardian.

People who apply for asylum typically wait two to five years to be interviewed by an immigration official (and wait even longer for a decision about their case). They also often wait more than six months after applying for protection to get permission to legally work in the United States. The government is working to reduce such wait times, but there is a large backlog. In the meantime, asylum seekers and their families live in limbo, which often contributes to lower earnings and increased anxiety.

Different standings, benefits, and services. In addition to the right to live and work in the United States, a person’s immigration status is a key factor in determining eligibility for public benefits and services. Refugees, asylees, and certain other immigrants with humanitarian protection may receive Medicaid, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Refugees receive additional services to support their initial adjustment to the United States, such as help with school enrollment. Immigrant families who do not get these initial supports often rely on family members, friends, or other informal supports to navigate the school enrollment process, or they attempt to do so themselves, which can be challenging.

Congress passed laws in 2021 and 2022 to support Afghan and Ukrainian parolees in the United States. Both groups are eligible for long-term integration services and public benefits and services such as Medicaid, TANF, and SNAP. Afghans who arrived through the Operation Allies Welcome program can also receive help with their initial adjustment period. In May 2022, the federal government announced additional funds to support schools in promoting certain Afghan students’ academic performance and integration.

Immigrants granted parole for a year or longer, certain survivors of domestic violence, and many lawful permanent residents (also known as green-card holders) only meet the immigration eligibility requirements for Medicaid, TANF, or SNAP after a five-year waiting period. Immigrants with employment-based visas, parole grants for less than one year, TPS, unauthorized status, and certain others are mostly ineligible for full benefits under these programs, though there are a few exceptions such as emergency medical services, immunizations and testing for communicable diseases, and certain disaster relief programs.

Children can qualify for several benefits and services regardless of their immigration status. These include Head Start, Early Head Start, and some federally funded childcare services; free and reduced-price school meals; the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC); and the Maternal, Infant, Early Childhood Home Visiting (MIECHV) program. In some states, children under age 14 who have a pending asylum claim may qualify for Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program. Older youth and pregnant immigrants who meet additional criteria may also qualify for these health benefit programs in certain states.

What Can School Leaders Do to Help?

While schools cannot ask enrolling families about their immigration status, school personnel can refer families to resources, benefits, and services. Some schools collaborate with local refugee resettlement agencies and community-based organizations that work directly with immigrant families. Such agencies could provide multilingual informational pamphlets to school offices and district enrollment centers, set up tables at parent information nights, or even hold office hours on campus. Additionally, bilingual and bicultural family liaisons can serve as trusted sources of information to families and staff.

Hiring bilingual and culturally competent staff and reinforcing a positive and assets-based mindset among their staff are among a principal’s most important roles when it comes to creating a welcoming environment for immigrant children. In particular, when students enroll in schools (rather than at a centralized location in the district), principals should ensure that front office staff are bilingual and know how to use interpretation resources for languages they do not speak, understand rules around enrolling immigrant families, and are comfortable working in a multicultural and multilingual environment.

Going further, especially in schools that enroll refugee and asylee children, principals may consider schoolwide training in trauma-informed approaches to communication, discipline, social-emotional learning, and other aspects of school life. And to ensure parent engagement, schools should have systems to track the language access needs of families, provide timely and accurate translations in accordance with civil rights law, and ensure two-way communication—informing parents about school systems and expectations and sharing home knowledge and cultural norms with educators.

Finally, administrators must carefully weigh the needs and strengths of their populations and the capacity of their school system when designing effective instructional programs, especially for immigrant students arriving in secondary grades. Ensuring students have language and content-learning supports—while also accessing courses they need to graduate—can be a challenge and requires careful planning by administrators and counselors. Administrators should also consider how federal funding sources—including but not limited to Title III grants for the education of English learners and immigrant students—can be used to tailor instruction and provide linguistic and academic enrichment.

Julie Sugarman, PhD, is senior policy analyst for PreK–12 Education at the Migration Policy Institute’s (MPI) National Center on Immigrant Integration Policy, where she focuses on issues related to immigrants and English learners. Essey Workie is the former director of MPI’s Human Services Initiative. Grace Leung is an intern with the National Center on Immigrant Integration Policy.

References

Capps, R., Gelatt, J., Ruiz Soto, A. G., & Van Hook, J. (2020, December). Unauthorized immigrants in the United States: Stable numbers, changing origins. migrationpolicy.org/research/unauthorized-immigrants-united-states-stable-numbers-changing-origins

Migration Policy Institute. (2021). Children in U.S. immigrant families. migrationpolicy.org/programs/data-hub/charts/children-immigrant-families?width=1000&height=850&iframe=true

Migration Policy Institute. (2019). U.S. immigrant population by state and county. migrationpolicy.org/programs/data-hub/charts/us-immigrant-population-state-and-county

Migration Policy Institute. (2019). United States: Language & education. migrationpolicy.org/data/state-profiles/state/language/US

Sugarman, J. (2021, March). Funding English learner education: Making the most of policy and budget levers. Migration Policy Institute. migrationpolicy.org/research/funding-english-learner-education-policy-budget-levers

Sugarman, J. (2019, June). Legal protections for K–12 English learner and immigrant-background students. Migration Policy Institute. migrationpolicy.org/research/legal-protections-k-12-english-learner-immigrant-students

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Refugee Resettlement. (2022, May 9). Afghan refugee school impact: Support to schools initiative. acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/orr/ORR-PL-22-12-ARSI-Support-to-Schools-Initiative.pdf