Fit to Lead: September 2022

In the wake of the pandemic and with the “great resignation” intensifying staff shortages, there is little question that it is a tough time to be a school leader. Indeed, a nationally representative survey released in June by RAND Corporation found that teachers and principals are not only under more pressure than before the pandemic, but they also have lower reported well-being than other working adults. Is there any way we can stop the cycle of increased stress and high turnover that doesn’t rely on waiting for district and state policymakers to devise a plan?

In our recent journal article “(Re)Envisioning Mindfulness for Leadership Retention,” published in The Bulletin, we sought to address the common thread of stress underlying both a poor sense of well-being and high rate of turnover among school leaders. While the demands placed on educators are real, how these demands are psychologically interpreted is a key aspect of addressing stress, well-being, and ultimately turnover.

For example, research consistently shows that stress is not caused by students, budgets, or policies—it is caused by the sense of unreasonable expectations, interpersonal conflicts, and a low sense of personal agency.

And while mindfulness is a popular stress-reduction option practiced by some individuals, research shows that it can have exponential benefits when it is collectively practiced across an organization. However, schools—and many educators—have been slow or even resistant to mindful approaches for improving well-being and retention. We believe this resistance is partly because of how schools operate, and partly because of how educators construct their professional identities. Below, we share strategies to overcome the social and organizational hurdles to adopt mindfulness programming in your school, with the goal of stopping the vicious cycle of stress, dissatisfaction, and turnover.

A Mindful Approach

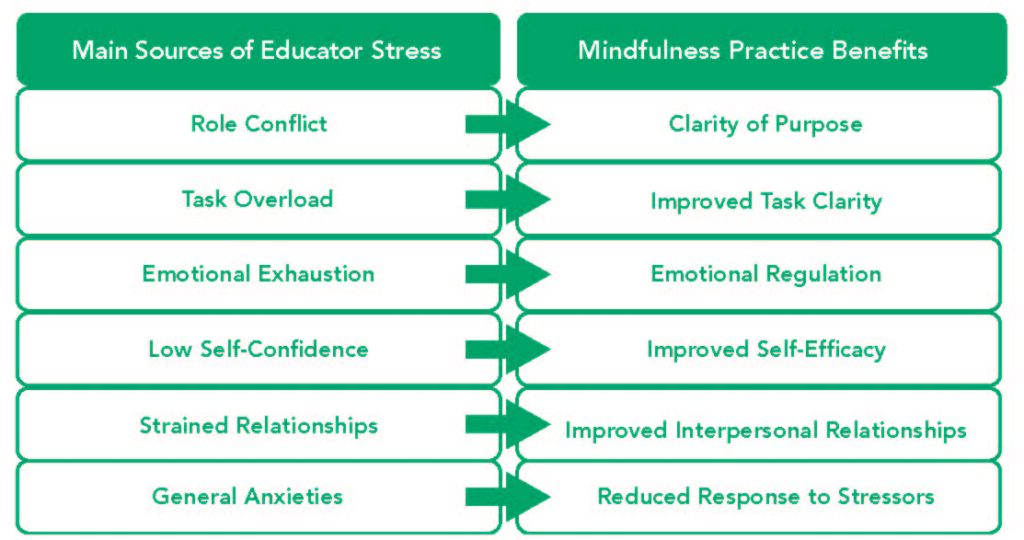

Research shows that mindfulness—the deliberate practice of mentally regulating our responses to external stressors—can directly address the major causes of educator burnout and turnover in the psychological realm where they are most felt. We combed through the research on sources of educator burnout and turnover and found that for just about every source of stress, mindfulness research has shown distinct psychological benefits to address these sources. (See the figure below for a list of these sources and benefits.)

Mindfulness practice, at its core, is about finding a way to focus on the present moment and experience the sense of well-being that comes with recognizing one’s place right here, right now. Mindfulness can include personal meditation but also reflection, self-inquiry, and awareness of our beliefs, motives, and feelings. The following are basic mindfulness practices:

- Attention to breath

- Reflection on daily intentions

- Yoga or slow stretching

- Journaling about mental state

- Mindful eating or walking

- Focusing on the absolute present

Why Is It So Hard to Incorporate Mindfulness in School?

Despite the generally prevalent knowledge of mindfulness as a stress-reduction tool, formal mindfulness programs have not been widely adopted by schools. First, mindful attention can be difficult to carry out in the school environment. There is little time to sit quietly in a school and rarely a space free from interruptions.

Second, many educators feel there isn’t enough guidance or support to establish a sustainable practice and simply don’t know where to start. There is little time to research a consistent practice or curriculum, and many want to know it is a wise investment of time.

The third—and perhaps the most difficult hurdle—stems from the basic working culture of schools and leadership. In a world of performance and outcomes, spending time focusing on your breath without a specific goal seems out of line with the spirit of trying to raise student achievement. When there are so many priorities each day, spending time on your sense of awareness can seem either selfish, a waste of time, or both.

But here is the catch. Mindfulness practices are right in line with successful education and school leadership. Research is clear that regular mindfulness practices not only reduce the specific sources of stress and burnout that lead to poor performance, but they also improve the dispositions and skills related to successful teaching and school leadership.

Moreover, mindfulness practices may have a considerable return on investment. Estimates have shown that the loss of a teacher can cost upwards of $25,000 and the loss of a principal can total more than $70,000 in administrative costs—not to mention the breaks in learning, onboarding time, and disruptions to social and professional connections. Given that formal mindfulness training programs for schools typically cost between a few hundred and a few thousand dollars, there may be an exponential return on investment through any improvements in retention. Some districts that have embraced and sustained regular reflective practices for school leaders have shown nearly double the retention rates.

In this way, not only is practicing mindfulness good for reducing personal stress and improving psychological well-being, it is also in line with school and district goals by promoting strong leadership, healthy working cultures, and engaged educators. Most importantly, this is a relatively low-cost intervention for improving performance and retention that is not dependent on the characteristics, resources, or policies of the school.

What Does a Robust Mindfulness Program Entail?

While integrating mindfulness into the workplace can begin with a personal approach, many leaders have found it not only beneficial to build mindfulness practices into their daily work routines, but also to share the benefits with others in the school. After all, building a community of practice helps keep one another mindful and enables everyone to share thoughts and insights and collectively work through challenges. Fortunately, there are many programs available to help schools design and build mindfulness routines that work with the unique structure, time, and goals of the school or district.

One of the most research-backed frameworks is mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), which utilizes a tailored approach of weekly group classes, silent retreats, daily home assignments, group reflection and dialogue, and individual self-assessments. According to the MBSR framework (mbsrtraining.com), a quality mindfulness program seeks to cultivate seven attitudes:

- Non-judgment

- Trust

- Patience

- Non-striving

- Beginner’s mind

- Acceptance and acknowledgment

- Letting go

Practices may include a day-long facilitated retreat to teach techniques, weekly group reflection sessions, and daily exercises involving journaling, shifting awareness, body scans, breath meditation, stabilizing attention, or light yoga.

Building a Mindful Organization

So, how can districts and school leaders find support for mindfulness programs and integrate them into regular school practice? The first key aspect is to explicitly recognize that mindfulness practices are not the opposite of productive practices. They are, in fact, complementary. From this position, several steps can help build a mindful school:

Emphasize Return on Investment (ROI) potential. As noted above, proactive investments of time and resources will more than pay for themselves with improvements in educator well-being and commitment, as well as reductions in burnout and turnover. This can be a high-leverage retention strategy even when budgets are tight.

Align with school mission and vision. Recognizing that mindfulness can be an integral pathway toward improved well-being and working relations, framing mindfulness within the school mission and vision may help garner support for programs and address others’ resistance to the practice as not being in line with their professional identity.

Integrate into the school’s Continuous Improvement Plan (CIP). If improving school climate, socio-emotional outcomes, or retention are part of your school’s CIP, recognizing mindfulness as a research-backed strategy can help establish regular practice and align the program with specific school needs. Aligning an MBSR program with the goals of the CIP can help with funding support, buy-in, and monitoring.

Collect data aligning to organizational goals. In line with the above strategies, collecting data on mindfulness practices will help integrate them into the school and ensure their sustained support. A key point here is to recognize that mindfulness outcomes are often indirectly supportive of broader educational goals. For example, mindfulness may improve interpersonal trust, which in turn may improve working conditions and student achievement.

Be clear about the holistic approach. As noted above, non-striving is a key component to successful mindfulness practices, meaning there should be no personal expectation of any specific outcome when conducting the practice, nor should it be treated as just another task to be completed. This is often not the approach taken in goal-oriented environments and appears to conflict with any emphasis on goals, data, or ROI. However, such a conflict is really a conflation of doing mindfulness and what mindfulness does. To make a sports analogy, softball players don’t stretch before games so that they win, they stretch because it supports better play, which may lead to winning. Mindfulness is a holistic approach to improving schools, and it is important to be clear that mindful practices should be enjoyed simply for what they are—any benefits are just bonuses.

Pilot with a core group. Any new program will face hiccups, delays, and pushback. By finding a small group to pilot a mindfulness program for a few months, many of the barriers may be discovered and dealt with before any program is widely promoted. This can also help to build a group of mentors for later implementation and support.

Explicitly address the secular nature of the practice. Mindfulness is often written off because of the perception that it is religious or conflicts with someone’s current beliefs. At its core, however, mindfulness is a tool that is completely secular in practice. This caveat may need to be stated openly, emphasizing that it is a research-backed practice supported by clinical and empirical psychology.

The Takeaway

For district leaders, investing in school mindfulness programs may have considerable benefits in both leadership and retention. While investments in mindfulness programs should not be a substitute for other much-needed investments in our schools (or used to add further responsibilities onto principals’ workloads), such programs can be one strategy among many to improve school leadership and the teaching and learning environment, truly from the inside out.

References

Steiner, E. D., Doan, S., Woo, A., Gittens, A. D., Lawrence, R. A., Berdie, L., … Schwartz, H. L. (2022, June 15). Restoring teacher and principal well-being is an essential step for rebuilding schools: Findings from the state of the American teacher and state of the American principal surveys. Rand Corporation. rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1108-4.html

Pendola, A., & Kim, D. J. (2022, March). (Re)Envisioning Mindfulness for Leadership Retention. NASSP Bulletin, 106 (1). journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/01926365221079050

Andrew Pendola, PhD, is an assistant professor of educational leadership at Auburn University in Auburn, AL. Dong Jin Kim, PhD, is a lecturer at Dongguk University (WISE Campus) in Gyeongju, Korea.