Role Call: October 2023

Leadership is leadership. The same essential qualities and characteristics that exemplify what great leaders do pretty much stay the same. What changes are the tools, research, and societal shifts that impact the work.

At its core, educational leadership is about helping others achieve a common goal that improves learning for students. An important part of educational leadership is what I like to call “pedagogical leadership,” which encompasses all the ways to support effective teaching and learning.

As opposed to instructional leadership—which focuses on instruction (what the teacher does)—pedagogical leadership requires a broader view, which includes paying more attention to what the learner is doing and the supports needed for success.

The pedagogical leader works to create collaborative benchmarks that lead to continuous improvement across the system. Such a leader seeks a deeper understanding of how the brain works and research-based strategies that teachers can readily implement in their classrooms. Observations, both evaluative and nonevaluative, still have immense value, but the pedagogical leader invests time and resources into establishing ongoing and job-embedded professional learning for staff. And while working directly with teachers is of the utmost importance, empowering parents and guardians to assist in the process is vital.

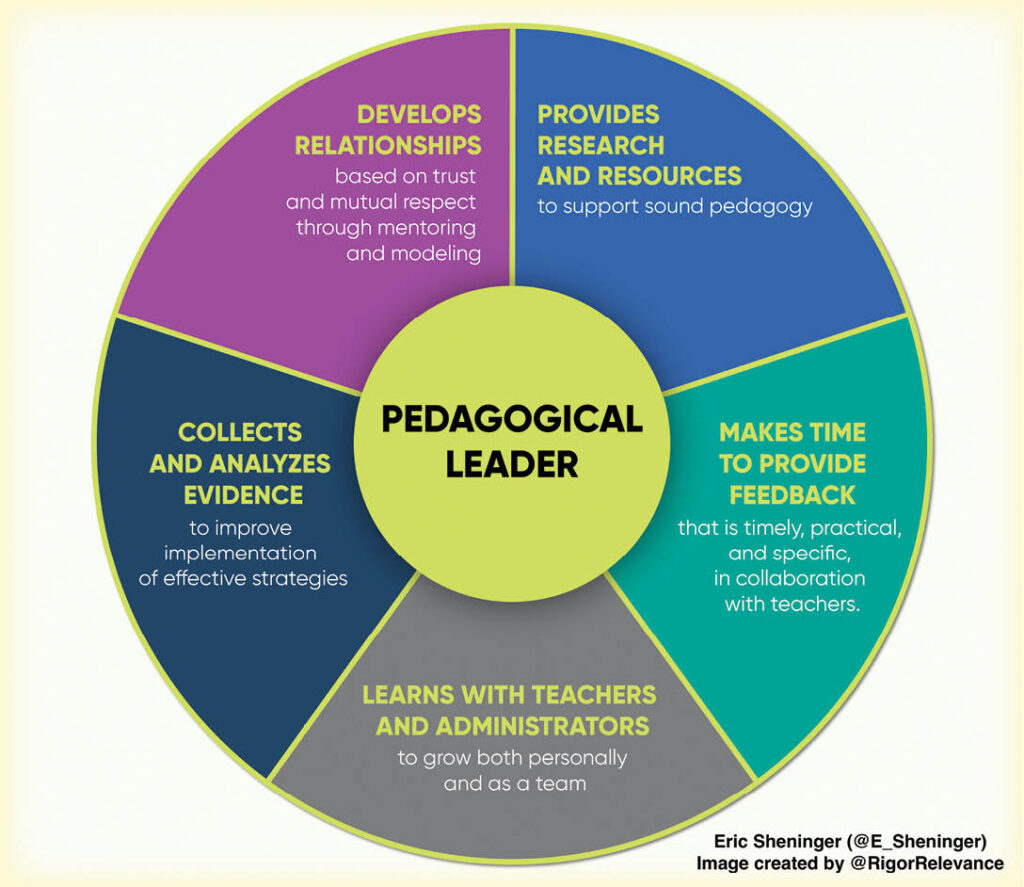

As outlined in the figure above, the pedagogical leader strengthens teaching and learning in their school by:

- Developing relationships based on trust and mutual respect through mentoring and modeling

- Providing research and resources to support sound pedagogy

- Making time to consistently be in classrooms while providing timely, practical, and specific feedback in collaboration with teachers

- Learning alongside teachers and other administrators

- Collecting and analyzing evidence to improve implementation of effective strategies

It’s one thing to explain these leadership attributes. It’s another thing to help school leaders develop them. To that end, I offer 10 steps that principals and assistant principals can take on the path to pedagogical leadership.

- Visit more classrooms. You can’t support areas where growth is needed if you are not aware of them. First, begin by increasing the number of formal observations conducted each year and sticking to a schedule to ensure that all teachers are observed numerous times annually, regardless of experience. Second, develop an informal walk-through schedule with your leadership team, mandating a set amount per day for each member, and track visits and improvement comments on a color-coded Google Doc. Visiting classrooms also allows you to collect qualitative evidence of effective practices in action.

- Establish norms. Establishing a shared vision and expectations for all teachers is crucial. You can do this by utilizing the Rigor/Relevance Framework to provide them with consistent, concrete elements to focus on when developing lessons and deciding which high-effect strategies to use. The framework is a lens through which teachers and administrators can examine all aspects of learning (curriculum, instruction, and assessment) and helps to create a culture around a common vision. Abolishing the routine of announced observations, having teachers provide artifacts of evidence to show the bigger picture since you can never see all that is done in a single observation, prioritizing the collection of assessments over lesson plans, and ensuring that data analysis is at the heart of professional learning communities (PLCs) can all be effective.

- Increase feedback. When observing lessons, always provide at least one practical suggestion for improvement, no matter how excellent the lesson. These suggestions should be clear, straightforward, actionable, and timely. For learning walks, consider curating data weekly and presenting it at an upcoming staff meeting. If you see something really great, consider following up that day with a phone call, handwritten note, or stop by the faculty member’s room to share verbally. Feedback is critical to encourage growth and development. It also sets up the leader to be an informal mentor for staff.

- Adopt an academic mindset. Improving professional practice as a leader is not the only benefit of being a scholar. It also enables you to have more effective conversations with teachers about their own growth, adding credibility to post-conference feedback. You can align critical feedback to current research by keeping a document of effective pedagogical techniques found in your readings. This approach saves time when writing up observations and improves relationships with staff. When in doubt, lean on Google Scholar or place a query using AI tools such as ChatGPT or Google Bard. Most importantly, be curious and ask questions. When it comes to leading pedagogical change, questions are often more important than answers.

- Model expectations. As I explain in Digital Leadership: Changing Paradigms for Changing Times, leaders should lead by example and not ask teachers to do anything they wouldn’t do themselves, especially regarding technology integration and improving practice. When a teacher struggles with assessments, provide or co-create an example assessment. Developing and implementing professional learning is also an effective way to lead by example and build better relationships with staff. If PLCs are in place, be sure to actively participate in one yourself with other building administrators.

- Prioritize growth. Attending at least one conference or workshop a year that aligns with a significant school or district initiative and reading one education book and one from another field, such as general leadership strategies or self-help, can yield powerful lessons and ideas. Growth can also come in the form of podcasts, webinars, and blogs. Creating or further developing a personal learning network through social media (Twitter, YouTube, LinkedIn, Instagram, Pinterest, etc.) is also essential to access 24/7 ideas, strategies, feedback, resources, and support. A personalized growth pathway enables you to learn anytime, anywhere, and with anyone.

- Identify opportunities to teach. Engage in this regularly throughout the year or by co-teaching with both struggling and exceptional teachers. I personally taught a high school biology class during my first few years as an administrator—an excellent case of leading by example. (For more on how this approach provides a better understanding of teachers’ changing roles in the disruption age, see my book Disruptive Thinking in Our Classrooms: Preparing Learners for Their Future.) Facilitating professional learning also places you in the role of teacher, which can help you garner greater respect and trust from your staff. By setting an example, a pedagogical leader strengthens relationships with staff members and better positions them to discuss and enhance learning.

- Reflect through writing. Writing has been a valuable tool for me to process my thoughts and critically reflect on my teaching, learning, and leadership work. Our reflections aid in our personal growth and serve as a catalyst for others to reflect on their own practice and develop professionally. Encouraging teachers to write brief reflections before post-conferences can foster a more collaborative conversation on improvement.

- Leverage portfolios. Incorporating portfolios in our observation process helps to provide more detailed insight into pedagogical practices over the course of the school year. Portfolios can showcase personalized learning activities, assessments, unit plans, student work, and other forms of evidence to enhance instructional effectiveness and validate good practice.

- Ensure inter-rater reliability. During the first quarter of each year, I collaborated with members of my administrative team to co-observe lessons. This allowed us to benefit from each others’ perspectives and expertise and provided opportunities for us to improve our pedagogical leadership skills and reflect on our observations. In my role as a coach, I have K–12 leaders visit classrooms beyond the grade levels they serve. For example, elementary school leaders conduct walk-throughs in secondary schools to provide feedback and vice versa. Gaining a perspective on strategies used at various grade levels is invaluable.

Talking the talk must be accompanied by walking the walk. It’s relatively easy for people to tell others what they should do. However, true pedagogical leaders take on the challenging work of showing how they themselves engage in the educational process. The best advice that I received long ago as a new principal still rings true: Don’t ask others to do what you are not willing to do or have not done yourself. If you want to improve pedagogy—and student outcomes—it all starts with you.

Eric Sheninger is the author of Disruptive Thinking in Our Classrooms: Preparing Learners for Their Future and Digital Leadership: Changing Paradigms for Changing Times. A former principal of New Milford High School in New Milford, NJ, he is a 2012 NASSP Digital Principal of the Year.