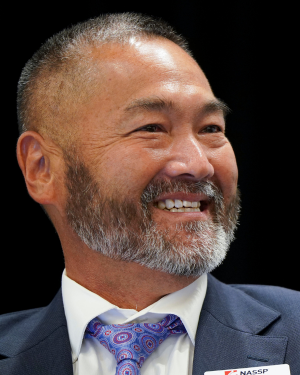

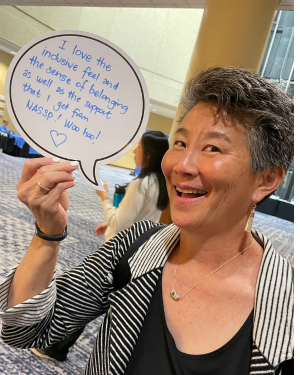

In recognition of Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) Heritage Month, NASSP CEO Ronn Nozoe and Managing Director of Leadership Development Robyn Hamasaki—both born and raised in Hawaii—talk about their backgrounds and issues related to Asian American educators and students in our schools.

Can you share a bit about your background and how it has influenced your career as an educator?

Ronn: I’m what’s referred to as Sansei, which is third-generation Japanese American. My grandparents immigrated to Hawaii, my parents were born here, and I was also born here. Education was always a high priority in our family, which included many educators. Starting with my auntie, who went into teaching when there were few other opportunities for women, to many other relatives in her generation, and down to my parents. My dad was a teacher, counselor, coach, assistant principal, principal, and central office guy, and my mother taught elementary school. But I wanted to go to law school so I could become a rich and famous attorney, and not have to work as hard as my parents. Of course, my plans changed during college when I started helping my classmates with their schoolwork, and I discovered I loved it.

Robyn: My roots go one generation farther back; I’m fourth generation born and raised in Hawaii. Like Ronn, I initially saw myself in a field other than education. I wanted to be a doctor and make lots of money. But in college I realized that I loved kids and teaching, which became my joy and my passion. You know how we say that the makeup of the educators should reflect their students? I realized how powerful that is during my career in Colorado. Asian families would tell me how safe it felt having an Asian principal and how their kids, especially the girls, would say they never really had Asian role models, and it shows they can grow up to be anything they want. It mattered that I was Asian.

When you were teaching or leading a school, how did you approach AAPI Month?

Robyn: At the beginning of my career in Boulder, the librarian and the teachers were very conscious about integrating more diverse authors into the library collections, and we would highlight different authors during specific months to bring awareness to the contributions of various groups. One of my favorite lessons involved our first graders comparing and contrasting different communities, including those of Japanese Americans. As part of that, I would write their names in Japanese lettering on a notebook they could take home and write in. They thought it was pretty cool. At the end, we all made sushi together. I’m authentically Japanese, and I was able to write with them and eat with them, which helped connect them to the Japanese culture they were studying. Most had never met a Japanese person before.

Do you think recognition months like this are a useful part of the school curriculum?

Ronn: Raising awareness about different groups and making sure kids feel like they are actually part of the conversation is great. For some kids, it helps them see themselves and realize how important their history and culture are to the fabric of society. And their classmates of different backgrounds can see that too. If we don’t recognize the different groups of people who make up this country, we can tend to forget the principles this country was founded on.

Robyn: What I struggle with is the idea that we’ll just focus on this for one month and then we’re done with it. There needs to be greater awareness where ideally, all these different groups, and their contributions to what our country is today, are embedded into a more integrated—and more powerful—approach throughout the whole year. But I do think as a starting point, these months can get people thinking more about diverse groups and how we can approach the curriculum differently.

Do you have any suggestions for principals, student leaders, and advisers about how to amplify and elevate the voices of students who are members of the AAPI community?

Ronn: I know this is an overgeneralization, but it is true that many AAPI students don’t want to speak up or speak out. Many of us were raised that way. Our people need to understand that it is OK to talk about their culture and their history. I think TV and social media have helped expose more people to our Asian Pacific Islander culture. That culture and the broader American culture are continually evolving, and it’s important that all groups continue to make themselves heard, even if it’s not what they are used to.

Robyn: I agree with Ronn on the point that we tend not to question authority, partly because there’s a respect for older people. So, it’s not surprising that an Asian student might not speak up in class, even with permission. In whatever way they can, schools need to establish structures and systems to encourage all students to make their voices heard and not just assume it will happen.

In honor of Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, NASSP’s Chief Engagement Officer Aman Dhanda joined Assistant Principal of the Year Finalist Bibi Davis and 2016 Digital Principal of the Year Winston Sakurai on Instagram Live for a conversation about Native Hawaiian culture in schools.